While much attention is focussed on the very rapid rates of growth on our urban fringes, the amount of infill development in established areas is often overlooked. In some parts of our cities, infill development is the major driver of new dwelling growth, particularly where there is an absence of large strategic sites. But how much infill can our cities accommodate and why do rates vary across the metropolitan area?

How do we categorise urban infill development?

Infill can take many shapes and forms. From the perspective of .id’s forecasting team, infill is generally considered to be sites that yield less than 10 dwellings. This then means that infill developments can include knock down and replace with villa units, or small scale new developments of up to nine dwellings.

In formulating assumptions around future rates of infill, id’s forecasting team will typically undertake a lot size analysis. This process involves looking at residentially zoned land that can be developed – it excludes larger development sites, recently developed parcels, strata parcels as well as parcels that are deemed too small for further subdivision eg less than 400 square metres (this can vary depending on the council). This analysis produces the overall number of parcels that can potentially accommodate new dwellings, and the forecaster then makes a call on a likely rate of development. This considers factors such as the age of housing, precedents eg are there examples of infill in the area, planning controls and strategies, and distance to public transport and facilities. The outcome is a likely number of residential parcels that than be developed, and the forecaster applies assumptions over the forecast period.

What does infill do to cities?

Though infill developments tend to be small scale, they often have the impact of achieving higher residential densities, particularly where a larger block is subdivided to create more than one new dwelling. Infill is often viewed of as a 21st century phenomenon designed to increase residential densities, but the astute urban observer will point out many examples of older villa units throughout the inner suburbs of Australian cities. Villa and townhouse type developments are popular with smaller households, but they also offer opportunities for older people to downsize within their local communities.

How much more infill can there be in our cities?

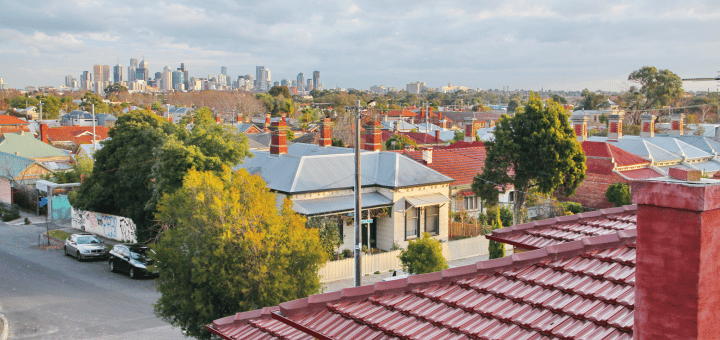

In fact, some suburbs have already accommodated so much infill that as a population forecaster, I wonder about how much more can be accommodated. The aerial photograph below shows a recent image of the inner Perth suburb of Carlisle. Located in the Town of Victoria Park, Carlisle is well serviced by public transport and has recorded modest rates of population growth in recent years. Its location near the CBD and Perth Airport makes it popular with young adults and it is this age group that has driven population increase in the area. This aerial photograph shows that almost all the older houses (generally interwar) have been replaced by villa unit/townhouse developments of 2-3 dwellings. In terms of population forecasting, the scope for future infill seems to be constrained, as these recently developed parcels are unlikely to undergo further development in the next few decades. If there is such a thing as an infill capacity, then a suburb like Carlisle can only grow through further intensification on newly created residential parcels or through the incremental process of suburban regeneration which can occur across several decades.

Source: Nearmap, January 2014

New suburbs in outer suburban areas have little scope for future infill, largely on account of their small block size. The aerial photograph below shows Tarneit, on the northern edge of Wyndham City Council. If you’ve been following Australia’s demographic story then you’ll be well aware that Wyndham is one of the fastest growing councils in Australia. New suburbs are being constructed very quickly with what was once grasslands now containing fully fledged suburbs. But the block sizes, and street layout in some of these new estates precludes future infill. In some cases the blocks are so small, but house sizes have not adapated and are often built right up against each other. Though it’s not a feature of Tarneit, curvy street layouts – so-called “dead worms” – also make further subdivision difficult. Once these types of suburbs are built out they are unlikely to add more dwellings to their stock (barring caravans and granny flats which are counted separately in the Census) unless there are major changes to the street and cadastral layouts. The Grattan Institute has previously suggested that new suburbs will have difficulty adapting to their changing population mix in the future due to their land use mix and street layout.

Source: Nearmap, October 2013

Where is there still infill opportunity?

But I don’t want to be the prophet of doom. It’s my job to be an astute observer of what’s happening in our cities and I can see plenty of potential for future infill in many parts of suburban Australia. However because .id produces population forecasts for small areas, we need to consider the evidence at a small geographic scale. Many suburbs, especially those developed in the post WW2 era close to public transport and other services, have huge infill potential. Sure the locals may not like it – in fact I was at a BBQ in one of Melbourne’s middle western suburbs recently and a comment was made about how there were too many houses in the street now and that it was difficult to get a park because of all the new units. Yet all I could see was the potential for more subdivision because the original houses were on large blocks and were starting to look at bit ordinary through their age and lack of maintenance – but I guess I see the city differently to most!

I also see that there are many opportunities for conversion of underutilised land – typically non-residential – that can be turned over for other uses. Some of this is already happening eg former industrial land being converted to housing but it can be contentious. Large scale developments often attract protests from local residents but we’re talking about small scale development here. Think about the suburb in which you live – how many vacant premises are there in your local area that have been lying idle for years? Who owns them? Surely if they’re well located they can be sold for housing or some other purpose? This is just a collection of thoughts – I’m not advocating for mandatory use of under utilised land, and in terms of infill, there may even be ways of subdividing in the future we haven’t even conceived of yet. In an era where we are trying to curb urban sprawl and create sustainable communities right across the metropolitan area, surely there is a better way of using some of this land?

In population forecasting, .id needs to understand and make assumptions about dwelling densities and urban infill rates across many areas. For more information about how we see Australia’s housing and land use changing, and its effect on population, talk to us about accessing our .id forecasts, available at micro or macro levels.