The ‘hard lockdown’ of public housing towers in Melbourne last weekend is one of the most drastic measures we’ve seen to date to curb the spread of COVID-19 in Australia. Glenn looks at the demographic profile of the people in these towers, to understand the challenges faced by them and the authorities charged with enforcing this lockdown.

See also: How to use our social atlas to plan communications with hard-to-reach and vulnerable communities

On Saturday (July 4th), the Victorian government announced that it was implementing a “hard lockdown” of specific public housing towers in Flemington and North Melbourne, to contain the spread of the coronavirus (COVID-19). Residents in these towers are currently not allowed to leave their homes, in an attempt to contain the spread of the deadly virus, and this is likely to continue for many days – initially 5 days, but it could be significantly longer.

ABC news has a good background on why there is a concern about COVID-19 in the towers and the challenges of the lockdown.

The history of Melbourne’s public housing towers

The towers are entirely public housing and were mainly built in the 1960s, by the state housing authority, which was then known as the “Housing Commission”, hence their most common name.

There are over 60 such high-rise towers in Melbourne, scattered through the inner suburbs in large blocks, but particularly in Fitzroy, Collingwood, Richmond, Carlton, Flemington, North Melbourne, South Melbourne and Prahran. Because they are high density and have common shared facilities within them, they make it physically difficult to contain the spread of COVID-19. This is the case with a lot of high-density housing, and these characteristics have been shown to contribute to the spread in places like New York City and parts of Italy (and the general lower density nature of Australian housing has been suggested as one reason that Australia has thus far been spared the worst of the pandemic).

Public housing towers have an extra level of difficulty because, by their very nature, they are housing substantially disadvantaged populations, which are among the most vulnerable groups both in health and economic terms, in the community.

A vulnerable corner of a prosperous suburb

The Flemington towers are part of the City of Moonee Valley. As we’ve mentioned in previous blogs, our social atlas tool (find a social atlas tool for your area here) is the best way to identify vulnerable communities on a range of measures.

And on almost every measure, this area shows up as highly vulnerable. Residents are likely to be more susceptible to COVID-19 due to substantial underlying health conditions, and there will be challenges in communicating here, due to poor English proficiency. Education and employment levels are also low, and access to the internet is poor.

This map from the social atlas covering the Flemington towers within the southern City of Moonee Valley, at the bottom right of the map, on Racecourse Rd. Note that not all these towers are in lockdown, but the largest buildings here are.

Multiple indicators of disadvantage

The SA1s covering these towers have among the lowest SEIFA index of disadvantage in all of Australia. SEIFA scores in these areas are in the 400-500 range, putting them in the most disadvantaged 1% of the nation. This is despite the City of Moonee Valley having a SEIFA of 1,035 – above the national average when taken as a whole Local Government Area – and Flemington as a suburb being at 855 – in the bottom 6% of the nation. This is where looking at characteristics at an LGA, or even at a suburb level can be misleading. Other parts of Flemington are quite high in socio-economic status, with SEIFA scores for areas just a few hundred metres from these public housing towers having SEIFA of 1,050+, well above average.

This clearly illustrates that the towers serve to concentrate disadvantaged communities in a small area, and are often the only place in inner-city suburbs which retain these disadvantaged populations. Other surrounding areas which don’t have government-provided housing are now highly gentrified with many high income and high education households.

Using the social atlas, we can pinpoint some of the characteristics of this public housing area which is really important for Local Government in understanding how to support these residents at this difficult time. Grouping the 5 SA1s that cover the area together:

- The combined SEIFA index of disadvantage is 449 (average for Australia is 1,000).

- 51% of households have low incomes (in the bottom 20% of Australia)

- There was a Census unemployment rate of 31.4%, and a workforce participation rate of 32%

- 73% of the population spoke a language other than English at home, and 21% have self-reported poor or no English proficiency.

- Almost 50% of households have no internet connection or didn’t answer that question on the Census form.

For the authorities managing the lockdown and those assisting residents through it, the language barrier may be the biggest challenge. With over 1 in 5 residents having minimal English proficiency (and there was also a high not stated rate on this question in the Census, so it’s likely higher), helping people to understand what they need to do to keep safe will require people fluent in many different languages and ideally with strong engagement with the local community. Though it’s not collected in the Census, we also know that many of the people in these towers are refugees (who make up around 8% of Australia’s migrant intake) – some from war-torn countries. Being confined to their housing with a police presence is likely to be quite distressing for this group in particular, so the lockdown needs to be handled sensitively as well.

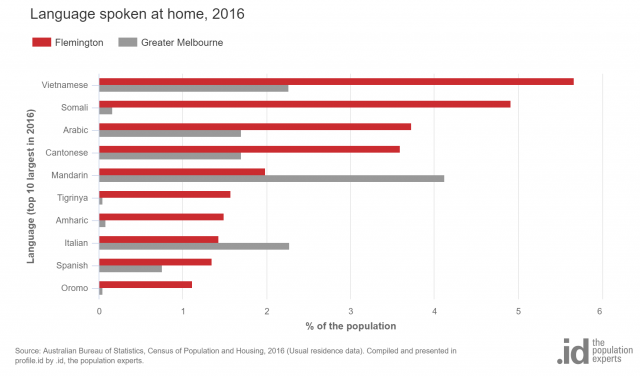

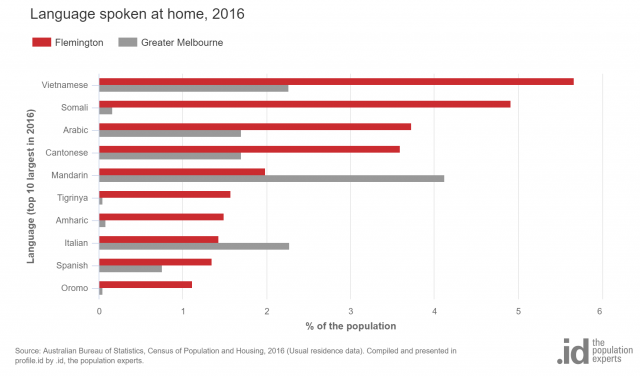

What are the most common languages spoken?

The main languages spoken in this area include some languages which are not widely spoken elsewhere in Melbourne, such as the Ethiopian languages Amharic, Tigrinya and Oromo. But the top two are Vietnamese and Somali, which are more widely spoken elsewhere. Arabic is also a major language, along with Cantonese from southern China. This is a truly multicultural community.

All this shows that there are significant challenges facing the residents of these towers, and those administering the lockdown. It’s a difficult time, and our hearts go out to those in this situation and we hope that it can be managed, and that everyone stays safe.