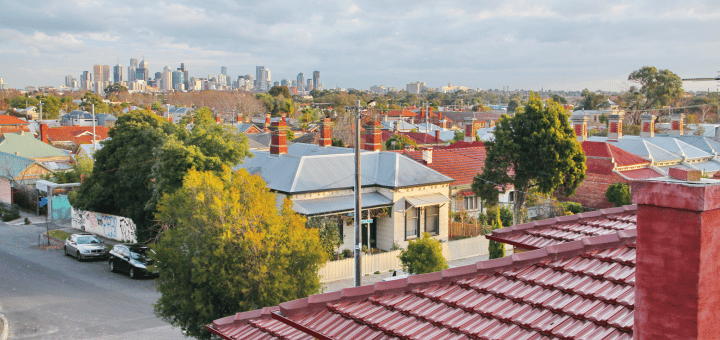

As you grow older, do you want to stay in the suburb you’re familiar with? Through our work with the City of Moonee Valley, we found that many residents would like to age in place, but some struggle to find suitable housing options as they reach retirement age. Providing options for older residents to downsize is a challenge in a number of local areas, but it also presents an opportunity to free up larger houses for families.

Discussions about housing in Australian cities often focus on younger households and families. However, in any comprehensive housing strategy, it is equally important to provide for the evolving needs of older people.

Catch up: Read the first blog in the series on medium and high-density housing for families

In the second article in our blog series on housing, which uses case studies to explore the relationship between dwellings and demographic change, we turn our attention to the mature end of the age structure – the age groups we often refer to as empty-nesters and retirees.

One of the trends having the greatest impact on our major cities is the ageing of the baby boomer generation. As this large group of people grows older, we are seeing a significant increase in the share of the total population reaching the retirement age groups.

The impact of this trend on the age structure of capital city populations is shown in Chart 1.

Click to expand – Chart 1: Age structure of Greater Capital Cities, 2006-2016 | Source: ABS Census of Population and Housing, 2016, 2006

Housing preferences change with age

More important, perhaps, is what this process means for the household composition of urban communities.

Ageing is naturally followed by changes in household formation; as a family moves through the household lifecycle, its children will eventually leave home to form new households, either as lone persons, in couples, or as a group. In effect, their empty-nester parents are also becoming a new household – an older couple without children.

In the future, this couple will evolve into a lone person household as one partner dies or moves to care accommodation.

As shown by the example of Margaret, our second case study from Melbourne’s Moonee Valley region, an older lone person is likely to have very different housing preferences compared to a young couple or family.

Despite this, many older residents will continue to occupy larger format homes that do not suit their lifestyles as they age. Chart 2 shows that around 42% of older lone person households across Metropolitan Melbourne live in separate houses with three or more bedrooms. In contrast, Margaret swapped her detached home for a two-bedroom apartment in her local area, and she hasn’t looked back since.

Why is this so important?

With a focus on the impact of ageing, Margaret’s story clearly highlights the importance of housing diversity in supporting a changing population.

Increasing the supply of smaller format dwellings suitable for older household types fosters two key demographic processes in urban communities:

At the retirement stage of life, it is important for many older residents to remain close to their family, friends and the community services they are familiar with. The availability of smaller dwelling types that are accessible and secure enables older residents to stay connected, without the excessive maintenance associated with a large detached home.

A sustainable suburb lifecycle depends on the access of younger households and families to suitable dwelling types that are close to employment opportunities. When empty nesters leave the home in which they raised their children, this creates a housing opportunity for a new young couple hoping to build a family in the suburb.

What does this mean for housing policy?

While ageing is always a talking point, the arrival of the baby boomer generation to retirement age is having a profound impact on the age structure of our capital city populations. Local housing policies must respond to this by considering the diverse housing preferences of residents as they age.

Providing options for older households to downsize can improve the quality of life of empty nesters and retirees, by reducing home maintenance and improving security. This depends on ensuring a share of new medium and high-density dwellings is designed specifically for the needs of older people, with accessible entranceways and secure parking facilities.

Housing diversity helps to address the scarcity of options for older residents who do not want to move to retirement accommodation. Crucially, it also organically frees up three and four-bedroom housing options suitable for younger couples and families.

Is this you?

If you’ve lived in the same suburb for a number of years, and are now considering downsizing, is there a suitable new home for you in your neighbourhood? Share your experience in the comments – we would love to hear from you.

Are you a planner?

If you work with council, read our case study Planning for future housing in Victoria Park.

Or, learn more about our free report on demand, diversity, affordability and supply in your area.