Generating an understanding of how social and economic issues impact specific demographics and places is a driving force behind .id’s work.

We endeavour to provide analysis that can help organisations make decisions to improve people’s wellbeing and/or attract attention to issues that need intervention.

.id recently worked with the Western Sydney University’s Centre for Western Sydney to conduct an analysis of youth unemployment for Youth Action – a peak body representing NSW’s 1.25 million young people and the services that support them. It was a chance to explore the increasingly challenging environment many young people face in outer suburban areas, impacted by access to jobs and education.

(If you’re involved with economic development at a local government level, you may find our economic health checks helpful in identifying the key challenges and opportunities in your local government area. Learn more here.)

The new landscape post-GFC

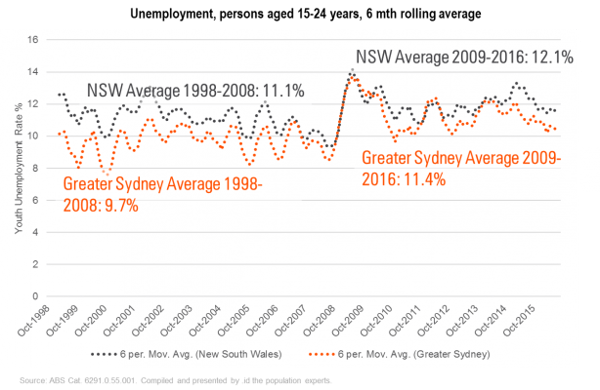

The weak economic conditions post-GFC had a sustained impact on employment in Australia. Jobs growth in the five years after 2008 was half that experienced in the five years before 2008.

Added to this was increased casualisation of the workforce. Although being part of a long-term trend, 84% of jobs in 1978 were full-time compared to 68% today, the five years post-GFC saw a considerable difference in growth rates, with 1.8 part-time jobs per full-time job created.

Young people entering the workforce at this time would have not only faced a situation of greater difficulty finding full-time employment but also finding any employment at all. Increasingly, they would have had to compete with displaced older, more experienced workers. In the last decade, jobs for 15-19 year olds fell by 97,700.

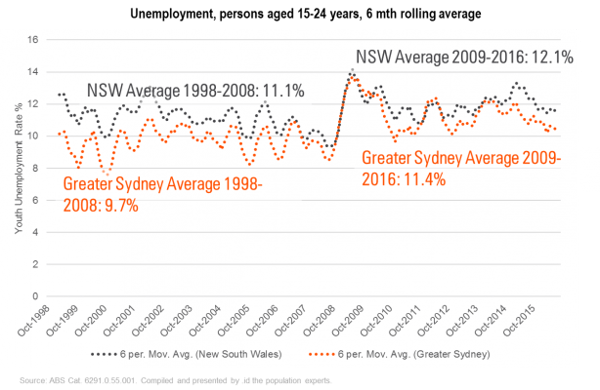

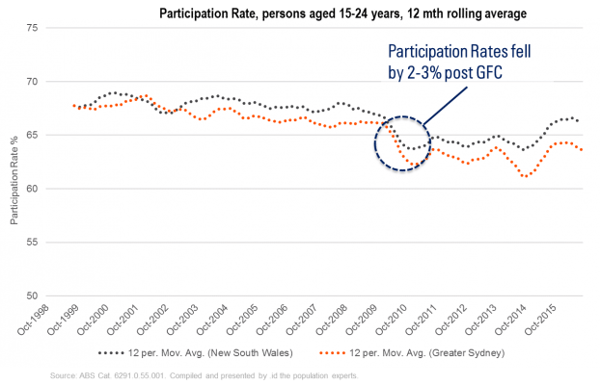

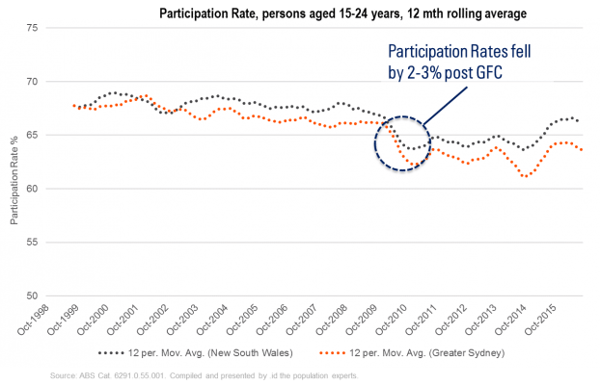

As a result of weaker employment conditions, unemployment amongst young people went up and participation rates fell. While some took the chance to pursue further study, others became disengaged.

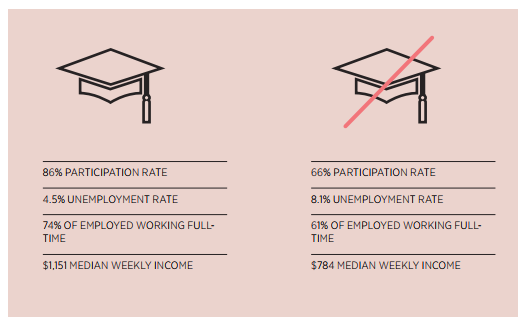

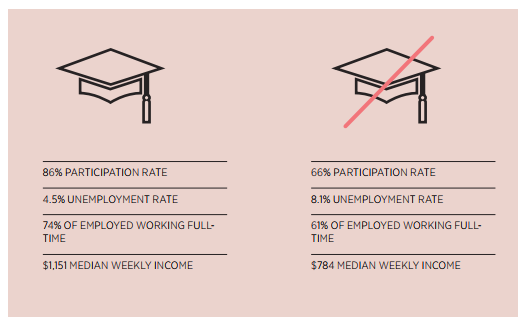

Pursuing extra study seems like a good decision even despite fears of growing white collar unemployment. In 2015, those people who had higher education qualifications were more likely to be employed, working full time and earning more.

Greater Western Sydney in focus

Given these macro trends, Youth Action was interested in exploring the characteristics of youth in Greater Western Sydney (GWS), an area of rapid recent growth. To explore employment and unemployment differences at a spatial level, we primarily used 2011 Census data.

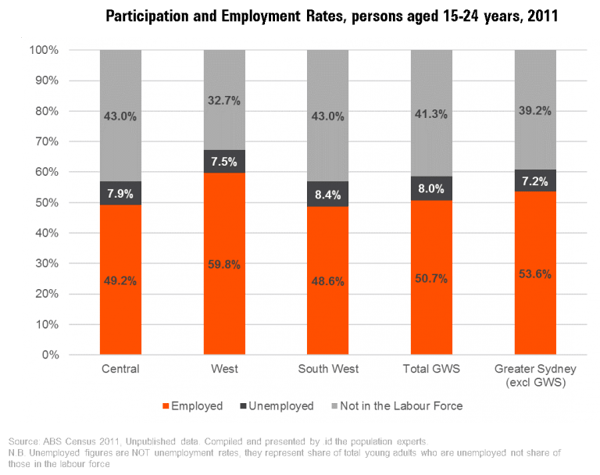

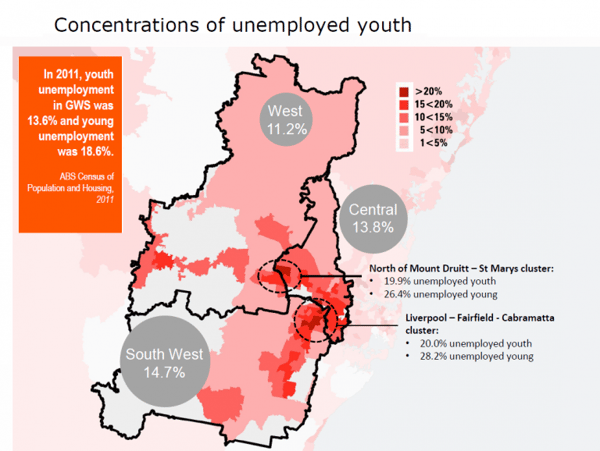

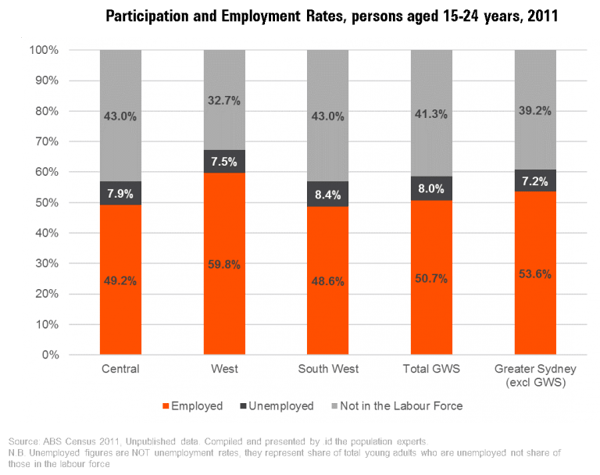

What we discovered was that while GWS youth were less likely to be employed than youth in the rest of Greater Sydney, there were great variances between areas.

For example, youth in the West sub-region (Blue Mountains, Hawkesbury, Penrith) had much higher employment rates, while unemployment was greater in the South West (Camden, Campbelltown, Fairfield, Liverpool, Wollondilly).

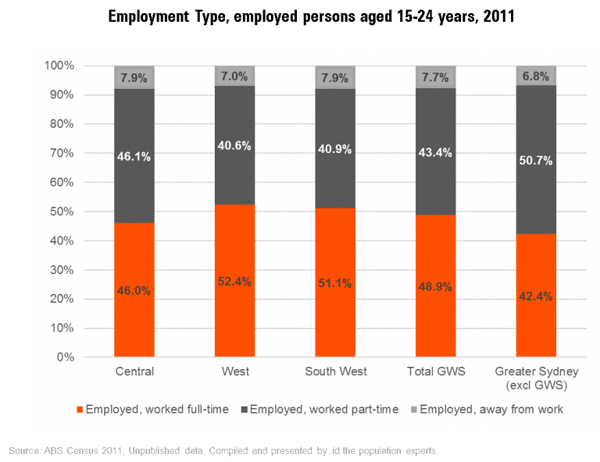

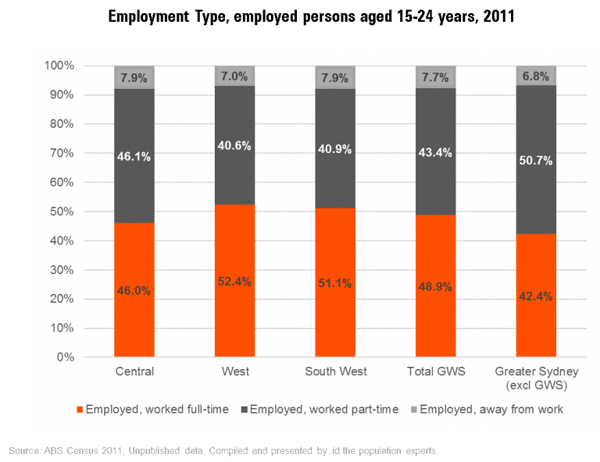

Of those employed, GWS youth were more likely to be employed full-time (48.9% of all employed) than their counterparts in other areas (42.4%). This is likely because 15-24 year olds in GWS are generally participating less in full-time education and more likely to be seeking full-time apprenticeships or jobs out of high school. The West and South West have particularly high rates of full-time employment.

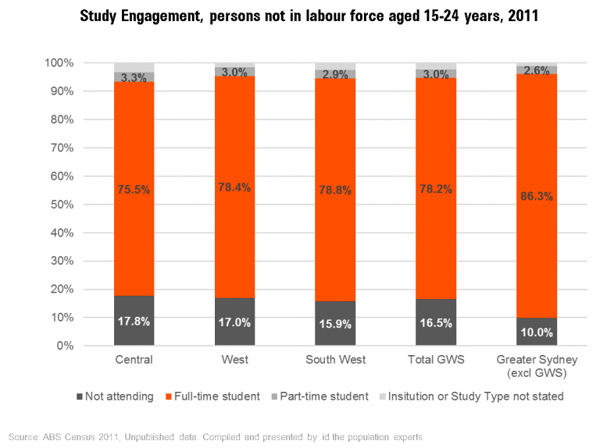

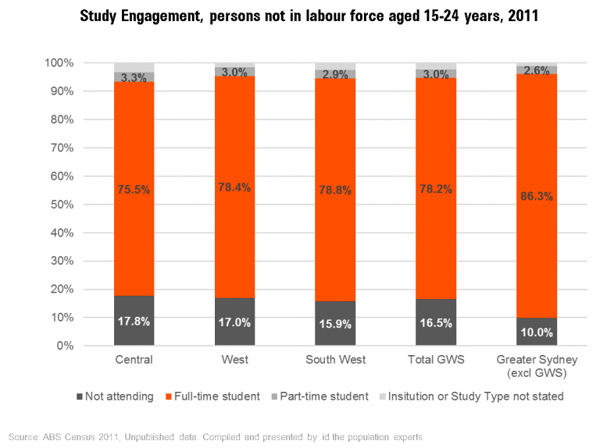

For those not in the Labour Force, GWS youth were less likely to be in full-time study than the rest of Greater Sydney.

Or, as our colleague at the Centre for Western Sydney, Professor Phillip O’Neill, put it –

“For Western Sydney to achieve the full-time education participation rate of 86.3% (measured for the non-Western Sydney portion of the metropolitan area), an additional 8,677 youth in Western Sydney should have been full-time students in 2011. This is the equivalent of an additional 580 full TAFE classrooms.”

Given the decline in availability of full-time jobs for young people and the increasing need for qualifications, it would appear GWS faces a growing challenge of improving education attainment rates.

Spatial analysis

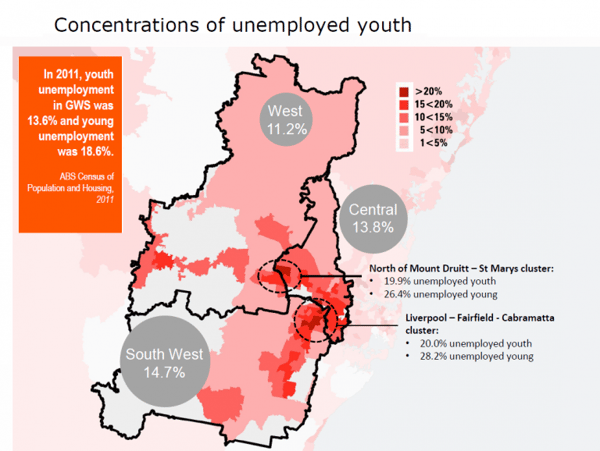

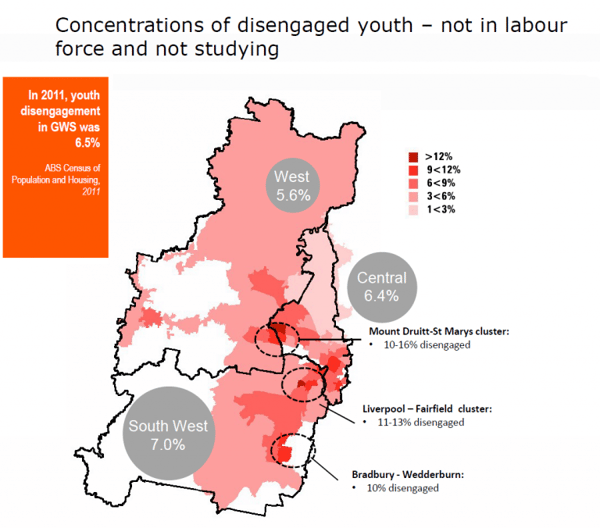

To greater highlight regional variations and identify more vulnerable communities in Greater Western Sydney we decided to map the data at smaller areas (SA2s). What it showed was that some parts of GWS actually experienced much lower rates of unemployment than the national average (12.2%) at the time. However, a couple of clear at-risk clusters emerged – an area around St Marys, Lethbridge Park and Mt Druitt, and an area running from Fairfield to Liverpool.

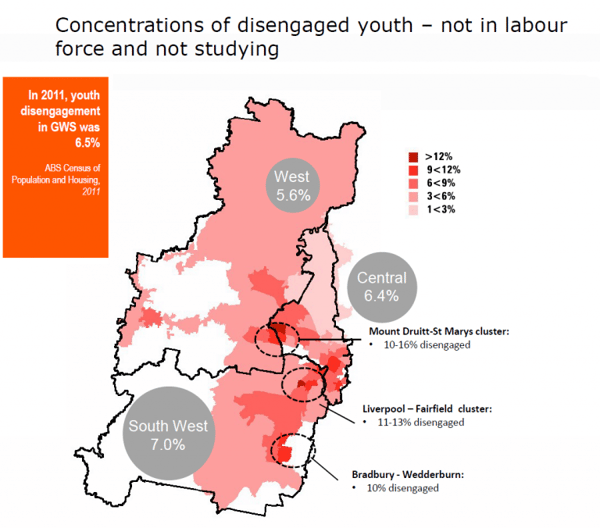

These locations also appeared amongst areas of high youth disengagement, which refers to those who are neither in employment nor looking for work nor studying.

Once again, given the size of GWS, there are also areas of very low disengagement within the region.

Cluster analysis

To provide a better understanding of the demographics of these vulnerable communities, we decided to compare the cluster areas to the GWS benchmark.

What we found was two different stories.

The first cluster had very low education outcomes with year 12 completion rates around 37-40%, and post-school qualification attainment at 16-17% – well below the GWS averages of 53% and 25% respectively. They also had higher rates of parental responsibilities, with 1-in-5 young women having children (compared to less than 1 in 10 for the rest of GWS). They came from households with lower incomes, low housing tenure, and low car ownership.

The second cluster represented areas of high new-migrant intake. The share of youth with parents born overseas was above 90%, compared to 59% for GWS. Education attainment was on par with the rest of GWS, though the incidence of low English proficiency was double the GWS average. They also came from households with low incomes and low car ownership.

These two case studies highlight communities with quite different needs in order to improve employment outcomes. One needs programs to improve school completion and pathways back to work, while the other possibly needs mechanisms to build local networks with employers and perhaps training to support improved integration.

Interestingly, both clusters had reasonable access to public transport options. However, the much lower rates of car ownership suggests that having access to a vehicle is more important for many young people entering the workforce, especially as entry-level jobs are not necessarily located along major transport networks.

Going forward

The findings from our analysis were presented at a round-table workshop hosted by the Centre for Western Sydney and Youth Action.

It was interesting to discuss ideas with policymakers and academics working in this area, but more importantly, we got to hear stories from youth in Western Sydney and their real challenges accessing employment and training. It brought home the reality of the issue and emphasised the urgency needed in developing programs and infrastructure to address it.

It will be interesting to see whether outcomes have improved for areas in GWS with the recent improvement of the New South Wales economy. Or perhaps the increasing amount of automation and casualisation in retail and other low-skill job areas has had an even more damaging impact on youth employment levels. The second release of data from the 2016 Census is set to be released in October and will perhaps help to answer these questions.

To read more of the report findings, head to the Youth Action site.

If you would like to explore economic or demographic issues in your area or broader region, contact our team of urban economists.

.id is a team of demographers, urban economists, spatial planners and data experts who use a unique combination of online tools and consulting to help governments and organisations understand their local economies. Access our free economic resources to help profile your local economy.