The Greece debt crisis has recently sparked some concerns over out-migration of young skilled adults in particular, but will we see an influx of Greek migrants in Australia?

Unless you’ve been sleeping under the proverbial rock in the last few months, you’ll know that the Greek economy is in a bit of strife. Not only is the country in debt, but there is high unemployment and increasing levels of social disadvantage. A recent article on the ABC news website suggested that the issues in Greece were resulting in thousands of Greek nationals flocking to Australia to seek work. This caught my eye for a number of reasons – firstly the supposed scale of this Greek migration to Australia (at levels not seen since the 1970s according to the Greek Orthodox Community of Melbourne), and also, it related to a blog I wrote about European migration about three years ago.

Of course Australia has been recording very high levels of net overseas migration in recent years, but despite the volatility of the numbers it has declined from the heady heights of 2008-09. In 2013-14, net overseas migration to Australia was 205,823, compared to 299,866 in 2008-09. These headline numbers are the ones that catch the media’s attention but the ABS does release a lot of more detailed data on migration that is not as well used in the community. One of the more interesting datasets is the Estimated Resident Population (ERP) by country of birth. If Greek people are migrating to Australia at levels not seen since the 1970s, then this should show up in the data set through an increase in the ERP of Greek born Australians. For the purposes of this blog, I’ve used the ERP as it captures that population living in Australia, rather than those who are here on a short term basis ie for education or working holiday. It also provides more indication of trends post 2011 Census.

In 2014, the number of Greek born people in the population was 119,950. This compares with a figure of 130,780 in 2000 ie a decline of 8.3% over the 14 years. The Greek born population has been in steady decline for longer than this and it’s easy to determine why. The original wave of Greek migration occurred in the 1950s and 1960s, and the community has been ageing ever since. In 1992, the median age of Greek born Australians was 51.2 years and in 2014 it was 65.7, making it one of the older ethnic communities. The young adults of that time are now approaching old age and their mortality is catching up with them, resulting in a decline in the number of Greek born Australians. If “thousands of Greek migrants” are coming to Australia, it’s either not yet evident in the data, or the number of deaths is higher than the number of arrivals.

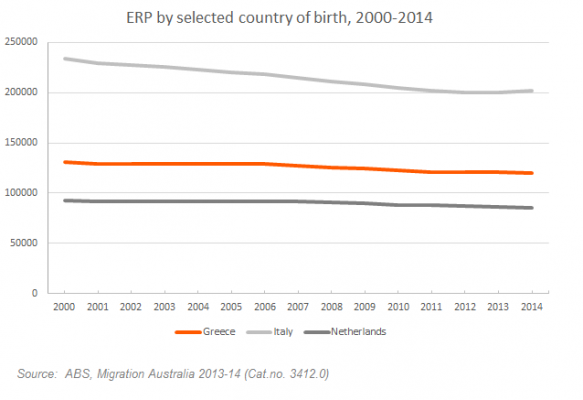

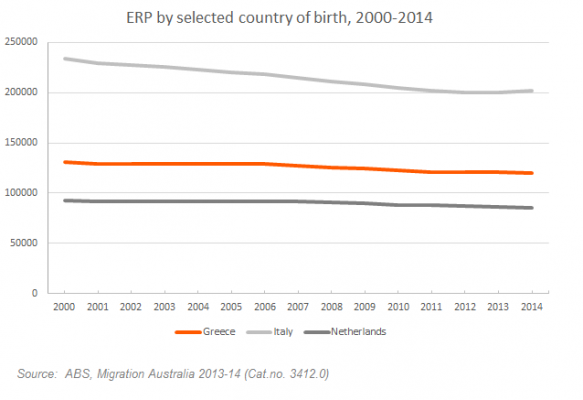

Ageing of migrant communities is not confined to those born in Greece, and the graph below compares the Greek born population with other European countries which were major sources of migrants in the 1950s and 1960s, namely Italy and the Netherlands. All three communities have recorded steady declines in their numbers since 2000, however, in the last few years, the Italian born community has started to increase again. The low point was in 2012 when Italian born Australians dropped below 200,000, but in 2014 they numbered 201,830 – a 1% increase. This has been a result of increased migration from Italy – probably new migrants and some returnees. Some of these may be moving to Australia for work purposes due to dire employment prospects in Italy, but certainly the increase in not in the order of thousands – more like hundreds. The median age of Italian born Australians had been increasing steadily up to 2011 and has now stabilised at around 69 years.

But of course birthplace is not the only measure of ethnicity – statistically it is also defined by language and ancestry. This data is readily available from the Census and provides a more solid understanding of ethnic communities in Australia. For example, the size of the community claiming Greek ancestry is about three times the number who were born in Greece. The initial wave of Greek migrants to Australia may be getting on in years, their children and grandchildren continue to define the community. In fact, the number of people with Greek ancestry in Australia, increased between 2006 and 2011 (from 364,990 to 378,160), despite the decline in the number of Greek born Australians.

I am certainly not trying to downplay the severity of the situation in Greece – certainly it has the potential to have major impacts on the global economy if the experts are right. There is no doubt that Greek people in a position to leave the country to find employment elsewhere will do so, but the reality is in a global economy, there are many options available – not just moving to Australia. The demand for skilled labour is very high around the world, and it’s just as likely that Greek people will move elsewhere in Europe (they are still technically part of the EU) than to Australia – despite the strength of the social ties between our countries. The evidence is clear – there is no indication in the population data released by the ABS that the Greek born population is increasing. Either they haven’t yet shown up in the data, or they consist of Australian born persons with Greek ancestry and this will be reflected in the 2016 Census data. Back in 2012 when I blogged about a potential new wave of European migration I suggested that it had to be seen in the context of rapidly increasing Asian migration to Australia. Though I haven’t presented any data here on Asian migration, countries such as China and India consistently show up as our major sources of new residents in Australia.

The detailed dataset on migration is available on the ABS website. Or visit our demographic resource centre to learn more about your local area’s population and demographic trends.