We at .id were saddened to learn of the recent passing of Professor Graeme Hugo. There aren’t many people in Australia’s demographic community who haven’t been influenced by his works – he was a prolific writer and speaker over many years. His influence was such that he was often quoted in the press, and he was also awarded an OA in 2012. While he has left a gaping hole in our community, I thought it was worth reflecting on the legacy he has left by looking at his area of expertise – internal migration.

Many years ago I completed an Honours thesis on retirement migration to the south coast of NSW. As part of my literature review I came across an article that Graeme wrote that has stayed with me ever since – “Using Census data to study elderly migration – problems and possibilities” published in the International Migration Review in 1987. In my opinion, it summarises beautifully the issues in the use of Census migration data generally – what we at .id call “the five year question”. Although I have lost the hard copy, I still paraphrase it today. I thought it might be worth reflecting on the points raised in the article because they are still relevant in 2015 (and presumably after 2016 if the ABS keeps the five year question intact on the next Census form).

- migration data as measured in the Census is an undercount for two reasons. Firstly, it only measures two points in time. In the case of the five year question, the data is only relevant to usual address on Census night and five years previously. For example, in answering the question on the 2011 Census form, your usual address in 2011 and 2006 would be counted, but any other moves made in the intervening period are not counted because they are not considered in the question. Secondly, it is not inclusive of the entire population, for example, people aged less than 5 years are not included in the data as they weren’t born five years previously. In addition, people who have died since the last Census are not included, even if they made a move in that time period.

- similarly, in the case of overseas migration, the Census essentially measures a one way flow ie inwards. This is because the Census is only relevant to people who are in Australia on Census night. If you lived in Australia in 2006, but were living overseas in 2011 (or even if you were overseas on holiday or business on Census night), you didn’t complete a Census form. Any moves you made will not be counted. However if you were living overseas in 2006, but in Australia on Census night in 2011, you will be included in the migration statistics. When we show migration charts on our forecast.id website, or in our presentations, it is important to remember that the overseas count is only an inflow, not a net move.

- characteristics of internal migrants are difficult to determine as the Census only measures those which were relevant on Census night, not at the time a move was made. In the case of retirement migration, we can only derive that it is such a move based on the characteristics in 2011 eg not in the labour force, aged 55 or over.

- the data does not specify the reason for the move – again this is something that can be derived from certain characteristics but it still needs qualitative data as a back up. Certainly many demographers would love to see a question on the reasons for moving on the Census form as it helps understand the drivers of change in a community. We often get asked why young people leave regional areas of Australia, but we can only surmise that it is linked to education and employment, and in fact other research has confirmed this.

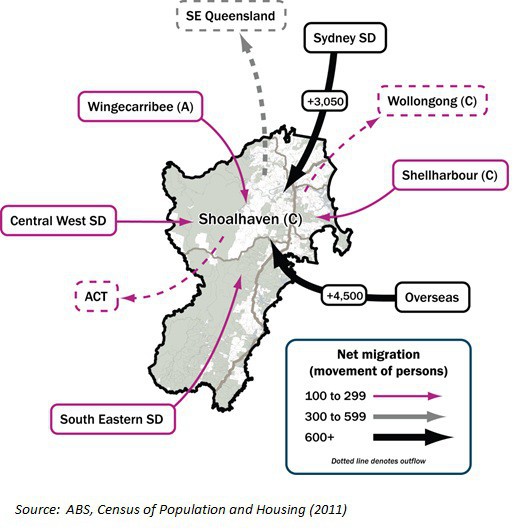

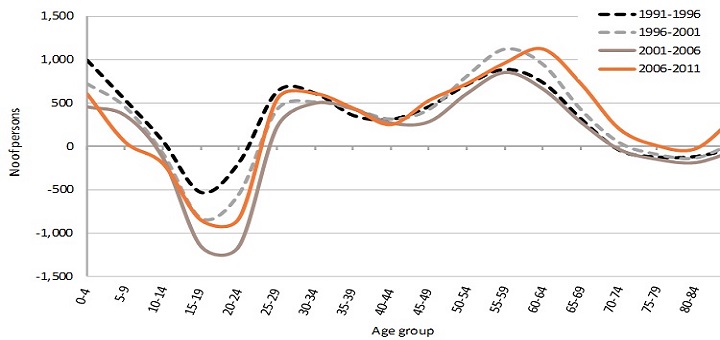

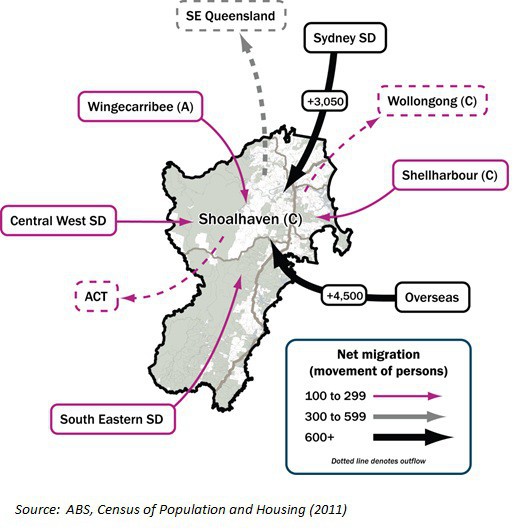

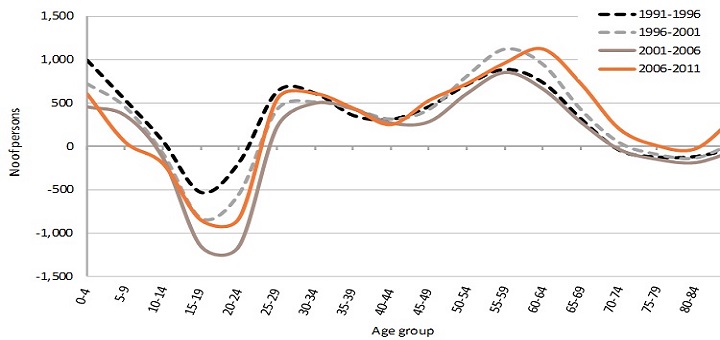

Despite these issues, migration data from the Census does provide a good indication into many of the demographic trends occurring in Australia. By way of illustration, the graphs in this blog show age specific migration for Shoalhaven City Council on the south coast of NSW for the period 1991-96 to 2006-11, and major net flows for the period 2006-11. The age specific migration data is derived from the five year question on the Census form and migration for 0-4 year olds is derived from the fertility rate. It’s clear that there are some distinct trends, such as –

- out migration of young adults, and in migration of families and especially retirees (as measured by age)

- significant inflow from larger urban areas such as Sydney

- the existence of local or regional moves, as indicated by movement into the City from the LGAs of Wingecarribee, Wollongong and Shellharbour to the north.

Migration data from the Census is also one of the few data sources in Australia on migration that it available for small geographic areas. From 2011 the data is available for SA2 regions, previously the smallest spatial unit was the Statistical Local Area (generally subsets of LGAs). For example, it’s data from the Census that confirms that from a spatial perspective, many moves are local ie within the same suburb or LGA, that outward moves within metropolitan areas tend to be in a sectoral direction ie inner north to outer north. It’s also useful for dispelling myths such as the predominance of “sponge cities” in the rural landscape.

Unfortunately I never got to meet Graeme Hugo. If I did I’m sure I would have been one of many people to tell him of the influence he had on their thinking about demographic issues. Some people leave legacies that extend well beyond their lifetime. Vale Graeme Hugo.