The definition of happiness and well-being differs greatly from one person to another. This doesn’t just apply to individuals but also to local governments and their communities. How can you effectively measure and plan for the happiness and well-being of your community?

My niece was amused by my hubby’s grumpy-old-man act and asked what would happen if there was a quota for grumpiness and he used it all up. How would he manage being cheery for the rest of his life? Would he be unhappy being happy? The temerity of youth!

Now my partner’s definition of well-being and happiness probably differs drastically from my niece’s (his revolves largely around mountain bikes, chainsaws, and our dog Steve), but in our house I think we all have the general aim of living happily.

It’s the same at community level. Working with local government I often get involved in discussions on how towns and cities are faring. Even though changes to the Local Government Act in 2010 repealed the responsibility of councils to identify and report on community outcomes (i.e. their community’s desired present and future social, economic, environmental, and cultural well-being), the goal of people living a good happy life is inexorably linked to good government – local and central.

How can a council’s activity not be a major contributor to well-being? And how can a major planning task like the current Long Term Plan avoid contributing to the future well-being of the district, city or region it is proposed for?

So whether you label it community outcomes or well-being or whatever, there needs to be a measure that adequately expresses the social, economic, environmental and cultural characteristics of a place and how it is changing over time.

At a global level the subject of well-being and of happiness rather than prosperity is attracting increasing interest. The United Nations has been moving away from GDP as a measure of a countries success because it is not sensitive enough to measure success in very different scenarios. A country or an area with a strong GDP may be languishing socially or environmentally.

The following abstract speaks to this issue and is taken from the 2009 Report of the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress chaired by Nobel Prize-winning economists Professor Joseph E. Stiglitz:

What constitutes a “good life” has occupied leading philosophers since Aristotle, and dozens of definitions of the “good life” are discussed in the literature. None of these definitions commands universal agreement, and each corresponds to a different philosophical perspective. Quality of life is often tied to the opportunities available to people, to the meaning and purpose they attach to their lives, and to the extent to which they enjoy the possibilities available to them. Quality of life research has identified a rich array of attributes – such as belonging, fulfillment, self-image, autonomy, feelings and the attitudes of others – that are associated with quality of life. Some of these attributes are intangible and difficult to evaluate. Others, however, have a more tangible character and can be measured in reasonably valid and reliable ways. In all cases, measuring quality of life requires consideration of a multidimensional array of indicators; at the same time, these indicators lack a unique metric that would allow simple aggregation across dimensions.

Stiglitz’s comments allude to a single measure to allow comparison and to combine the tangible with intangible. Two recent studies have had a stab at measuring “happiness” in such a way.

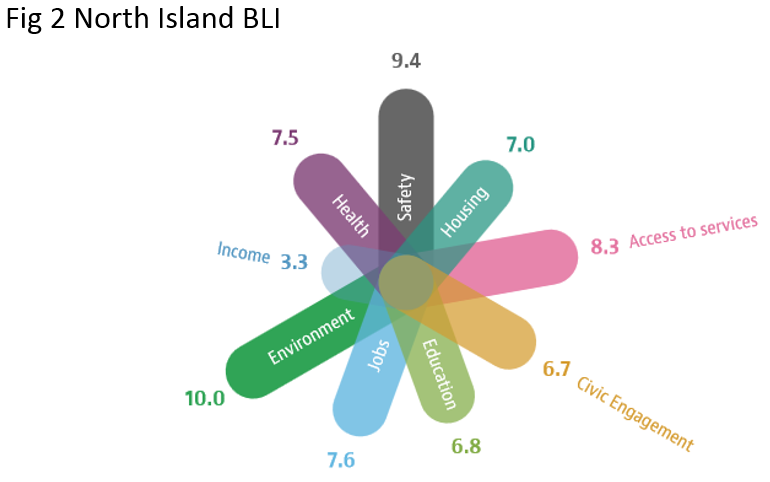

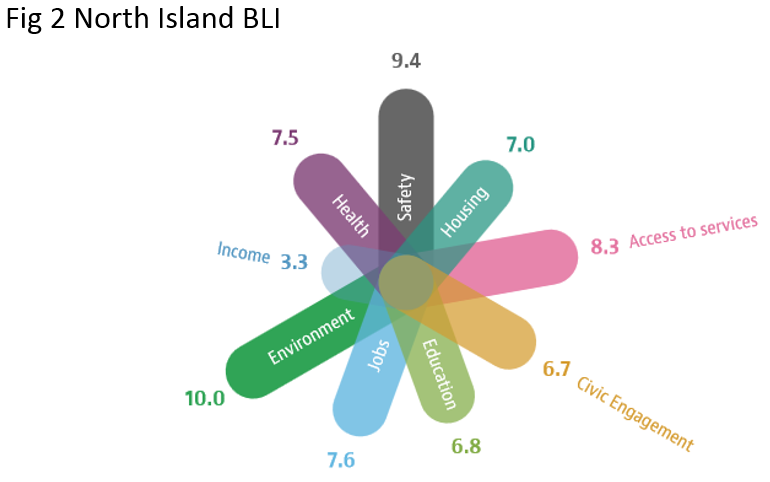

The OECD’s Better Life Index (BLI) considers wellbeing topics under two headings – material living conditions (housing, income and jobs) and quality of life (community, education, environment, governance, health, life satisfaction, safety and work-life balance). The OECD focus on member countries but also include Russia and Brazil. If you go to their website you can view the Better Life ratings for your country and in many cases area – see http://www.oecdregionalwellbeing.org/

The following figures compare the South and North Island of New Zealand.

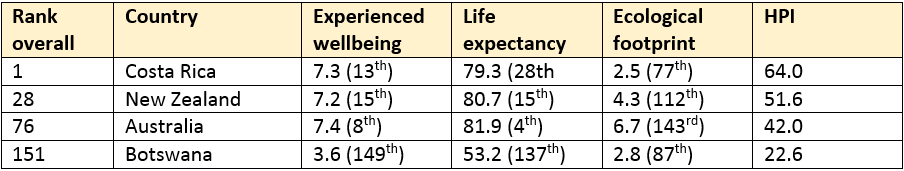

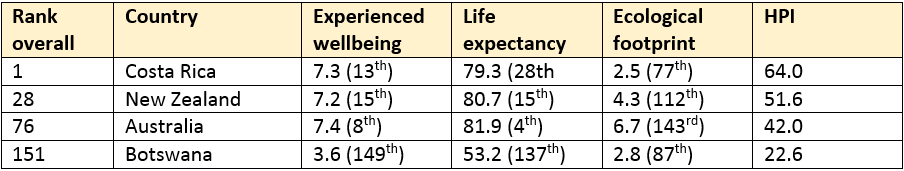

By comparison the Happy Planet Index (HPI) positions the environment in a very different role when assessing the wellbeing. Using a set of quality of life measures (e.g health as well as more subjective wellbeing measures like sense of vitality, personal resilience, relationships and belonging, and life expectancy) the HPI measures wellbeing per unit of environmental output (ecological footprint). Put more eloquently, the HPI identifies how efficiently countries use their finite physical resources to produce wellbeing in their citizens. In 2012 the HPI (see http://www.happyplanetindex.org/data/) assessed 151 countries for the third time and the top three countries in order were Costa Rica, Vietnam and Columbia.

The Happy Planet Index is illustrated in the below table with the highest rating country of Costa Rica leading the pack.

A strength of the HPI is that it reflects the diversity of countries. For example, the highest ranking countries based on their ecological footprint were Afghanistan (0.5), Haiti (0.6) and Bangladesh (0.7). In comparison the highest rating countries based on their wellbeing scores were Denmark (7.8), Canada (7.7) and Norway (7.6).

Whether you are considering your region’s wellbeing or your towns, a big part of your analysis will include using demographic indicators from the census – i.e. age, income, employment, housing, dwelling, education, qualifications etc. You will often be able to find the data for your town or region by visiting our community profile portal www.profile.id.com.au.

Mountain bike and chainsaw inventories are probably best conducted on an individual basis.