BLOG

What’s standing in the way of us building adaptable cities?

What’s standing in the way of us building adaptable cities?

As one of our most experienced population forecasters, Richard Thornton’s daily work exposes him to the many factors that influence when, where and how much growth occurs in different parts of Australia. In this piece, he highlights three factors that Australian planners need to reconcile – population growth, constraints to land use and development, and climate change, highlighting some of the structural challenges that make our cities less adaptable in the face of these realities.

Cop 28 has recently occurred, and given the increased pessimism surrounding meeting current targets and capping global warming at a 1.5C temperature rise above pre-industrial levels, it is increasingly likely that we are in the last-chance saloon to avoid potentially catastrophic warming. The implications of climate change are profound and will have far-reaching effects in Australia, a country with a long history of natural disasters, and already experiencing increased flooding, coastal erosion and fire risk linked to warming. All areas of our lives will be affected, and planning to deal with the implications and minimise further warming is an immediate challenge that needs to be addressed now.

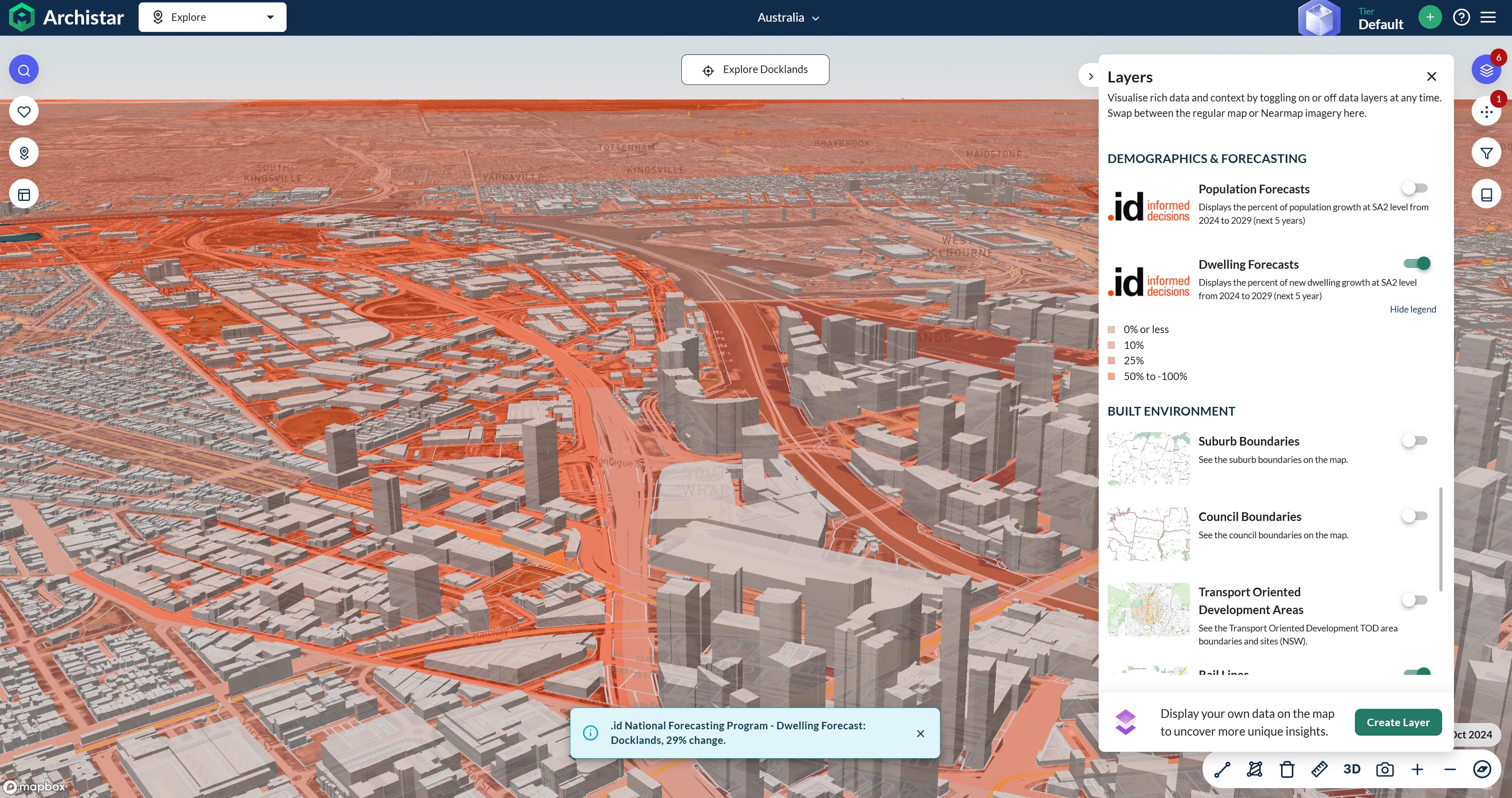

In my work as a population forecaster at .id, I’m particularly conscious of these factors. .id provides population forecasts nationwide from the national to neighbourhood levels. To this, we have mapped all currently identified future development opportunities across urban and regional Australia and monitor changes and rezonings. This analysis raises the question of how much of this identifiable supply will remain developable in the future, given flood and fire risk, and raises the critical question of how our future population will be housed. Poor policy decisions and outcomes on the type of development that takes place, where it occurs and will itself have effects on climate change, social justice, equity, and the future livability of our urban and rural environments. Housing our future population growth in a way that will be sustainable poses significant challenges to policy makers and developers, and I would argue that those risks remain largely unaddressed. Our built environment and catering responsibly for future population growth present essential components of any strategy to provide climate resilience.

Can we continue to house a growing population in low-density housing on our urban fringe?

We forecast that Australia will grow (conservatively) by an additional 9.6 million people over the period to 2046. Ignoring the arguments for a ‘big’ or ‘small’ Australia, the economic need for migrants is unlikely to change in the future, nor are the reasons for why people migrate.

A critical part of the research process for our population forecasting is a detailed assessment of the current housing stock and the forecast pipeline of future housing in each local area where we produce our forecasts. At our recent launch of forecast.id national, we presented the results of this research, which showed two-thirds of Australia’s forecast population growth over the next 25 years will be in our four largest capital cities.

Within our largest capitals, our forecasts show a high proportion of the forecast growth in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne will be 20 km or more from the CBD.

It is doubtful that the current pattern of development can be sustained in the medium to longer term, given future environmental risks with areas at risk of fire and flood hazard growing.

A recent example is the City of Blacktown where, as outlined in a recent Council update an identified capacity of 12,700 new homes has been reduced to 2,300, a significant reduction in land supply required to reach the State Government targets. As climate impact models are revised to deal with more extreme conditions, further areas will likely be found to be unsuitable for future development.

Additionally, there is the social justice argument – developing housing in yet more distant new suburbs without attendant infrastructure is likely to impact this further, potentially increasing disadvantage through providing housing in increasingly marginalised areas. Houses being built now in areas potentially at risk of extreme weather events could end up uninsurable, or in the event of a disaster, cost billions in recovery and economic impact, not to mention the lives lost or ruined.

Is the densification of our cities the answer?

We are producing the wrong type of housing in the wrong type of areas and are not equipped with policies and systems that can address the situation and investigate alternatives that support housing growth and address climate security.

The residential development pattern in our inner cities has not changed significantly since the 1950s. The market is governed by a strong belief that families want detached housing with a yard, whilst apartments are only marketable to younger professionals, students, and empty nesters. There have been many arguments that further fringe growth is not a desirable outcome and that the densification of our urban areas is the alternative, after all there are many countries where apartment living is widespread amongst all household types in urban centres. However, we do not build 3 or 4- bedroom apartments except at for the luxury end of the market. Consequently, the beliefs in what is commercially developable are self-reinforcing: given the lack of family-friendly and affordable apartments, demand is predominantly from young professionals and students. As a result, higher-density areas have few services catering for families therefore encouraging families to seek housing in new fringe housing where schools and facilities are provided. A good summary of the issues presented is contained in “Getting to Yes: Overcoming barriers to affordable family friendly housing in inner Melbourne’.

Arguably the market is unlikely to lead the way owing to the perceived financial risks; perhaps this is the role that our state governments should be playing, developing projects to prove the market.

Inevitably growth on our urban fringes will continue, but traditionally these have achieved relatively low densities, being dominated by detached housing with densities of around 15 to 18 dwellings per hectare. Where townhouses have been constructed, it has been in small pockets, and remains the exception rather than the rule in master-planned estates. There have long been arguments for a greater diversity of housing on the urban fringe (Michael Buxton of RMIT has long been a proponent), but without more aggressive planning policies requiring a greater proportion of townhouses and apartments, the development industry will rely on what they know will sell. Such requirements are needed as early as possible. As soon as releases have been sold to housebuyers, the opportunity to achieve higher densities is effectively lost for at least thirty years before redevelopment might occur.

But construction is also a major source of carbon emissions, how can we justify higher-density construction?

The construction of high-density dwellings is not a simple answer; new construction is itself a major source of carbon emissions. Currently the Australian construction industry is responsible for 18.1% of the national carbon footprint, totalling 90 million tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions every year There are strong arguments for retrofitting existing obsolete buildings rather than demolishing and rebuilding. The Victorian State Government has pushed for more retrofitting in its housing statement released in September, to convert obsolete office space into residential dwellings. Examples (albeit for commercial use) are the Quay Quarter tower in Sydney and the retrofitting of NAB’s former headquarters at 500 Bourke Street in Melbourne. Retrofitting of obsolete buildings also has the potential advantage of reducing the construction costs of apartments, roughly $3-4,000 per square metre in new build.

Of course, new buildings are necessary given the demand of population growth and this is where building and urban design are so important. The inclusion of green infrastructure, green walls and roof gardens and the inclusion of public space in the form of parks and street trees can help remediate greenhouse gas emissions, and this is an area where building and planning regulation can have a large impact. An example of a public strategy seeking to address this is the City of Melbourne’s Urban Forest Strategy.

Another area where climate impacts can be reduced is the type of construction materials that can be used as alternatives to the high carbon cost of concrete. There is significant literature on the costs and benefits of sustainable construction, as well as methods of evaluating the carbon cost of a particular construction to mitigate and minimise impacts.

How do we ensure that our urban environment can continue to adapt to the changing climate?

To cater for future growth and pressures on our environment, we should ensure that our built environment retains the flexibility to adapt to new market pressures and provide a diversity of housing stock into the future. This requires ensuring that the built form within inner and middle ring suburbs retain flexibility allowing future lot consolidation and the adaptation of areas to higher density forms. Unfortunately, past development practices have locked up areas, shutting the door for future higher-density redevelopment, or have ensured that the cost of that development means that current practices are perpetuated owing to costs.

Many suburban areas are subject to the opportunistic subdivision of single lots into villa units, of between four to eight dwellings. An example is the suburb of Innaloo in the City of Stirling (WA).

The photograph above shows how many of the original lots have been developed lot by lot into medium-density villa housing. This effectively prevents the future consolidation of lots owing to the fragmentation of titles, or even if there were to be consolidation, the additional costs of purchasing the land would make any redevelopment unsuitable for family-sized apartments.

This area of Perth is less than 9 km from the Perth CBD. Notably, the area outlined in orange is zoned for urban redevelopment, allowing greater residential density, but despite this, the potential for any significant development is highly constrained. There are examples of this outcome in areas of all our capital cities. Arguably many of these units do house families, but often in properties that have the traditionally identified drawbacks of apartments – in that they are small, have no backyard and are not family-friendly, but with the additional disadvantage of being nowhere near the types of amenities and transport routes that have justified higher density zoning. What is more, this type of development generally reduces existing tree cover, removing garden trees. The lack of tree cover and the potential for urban heat sinks can be seen in the photograph.

A response would be to introduce minimum densities, but there are very few examples where this has been done, and where it has made a difference to the development. Nevertheless, ensuring that neighbourhoods have some flexibility, both in terms of providing future development opportunities for a diversity of housing stock, and also proving the type of building stock that can be retrofitted to alternative uses and forms as required, rather than becoming obsolete and requiring demolition. One policy experiment by Maroondah City Council in Melbourne, to curb single lot development into units and achieve higher densities, is the option for homeowners to amalgamate their properties to allow development of up to four stories.

This article only scratches the surface of the issues that confront our cities. Our analysis and mapping of development opportunities will, as we continue to monitor it, hopefully reflect changes in policy for residential development and the housing of our future population, as climate risks are modelled, and policy evolves. However, if we are to ensure that we can house an additional 9.6 million people over the next 25 years, we need urgently to address these issues now and ensure that our cities remain desirable and safe places to live.

Richard Thornton

Richard has a background in urban planning, regeneration and social housing. He previously worked in the housing sector in the UK and for the Victorian Government. He produces population forecasts for local government areas in Sydney, Melbourne, Perth, Queensland, Regional Victoria and New Zealand. He regularly presents on the policy implications and challenges of demographic change for a variety of audiences on both sides of the Tasman. Richard enjoys spending time with his kids, camping and playing the piano.