BLOG

The PM’s population policy: a NOM event

The PM’s population policy: a NOM event

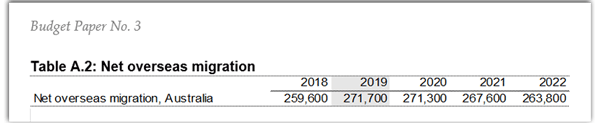

With last night’s budget, the Treasury published forecast assumptions about Net Overseas Migration (NOM) – the net effect of people coming to and leaving Australia. These figures contrast starkly with the Government’s recent ‘tough on migration’ stance when they announced their population policy in March.

We thought it was a good opportunity to look at who would be affected if the government did introduce a policy that reduced the number of visas available for people who want to come to Australia.

A 15% cut in the ‘migration ceiling’ – from 190,000 to 160,000 places – was a headline figure in PM’s well publicised ‘Plan for Australia’s future population’ last month.

However, with the release of last night’s budget papers, we saw the Treasury’s forecasts for Net Overseas Migration (NOM) remain between 240,000-260,000 in 2018, and hold steadily above 260,000 out to 2022.

Forecast net overseas migration to 2022

| Year | Net Overseas Migration |

|---|---|

| 2015 | 186,730 |

| 2016 | 243,830 |

| 2017 | 240,420 |

| 2018 | 259,600* |

| 2019 | 271,700* |

| 2020 | 271,300* |

| 2021 | 267,600* |

| 2022 | 263,800* |

* Table A.2 in Appendix A of last night’s budget papers

So, while the contrast in these figures tells a political tale, we think it’s a good opportunity to look at who doesn’t get to come to Australia if the government policy results in reductions to Net Overseas Migration.

Government-issued visas and Net Overseas Migration

It’s worth making the point that not all these 260,000+ net migrants would be affected by government policy.

The government can impact a portion of Net Overseas Migration by changing the number of temporary and permanent visas they issue, but as we’ll see below, that doesn’t make up the whole NOM pie.

Australian and New Zealand citizens come and go from Australia – these movements aren’t influenced at all by government policies on temporary and permanent migration visas.

Who makes up our ‘Net Overseas Migration’ numbers?

If you accept that limiting population growth from migration is one of the levers you can pull to ‘ease population pressures’ (read: bust congestion), even if that’s only a portion of forecast NOM, let’s take a look at who would be affected.

When you break down the categories of people who are coming to and going from Australia, it looks something like this:

| Temporary travellers | ‘Visitors’ who stay for less than 12 out of 16 months aren’t counted toward NOM, and therefore total Population (*see our note below clarifying a previous version of this explanation) |

| Temporary migrants | Students

Backpackers Skilled workers (457 Visa holders) |

| Permanent migrants | Skill (15%), Family (9%) and Special eligibility or humanitarian visas (6%) accounted for around 30% of Net Overseas Migration in 2017. |

| Australian and New Zealand Citizens | Government policy doesn’t influence or restrict travel by Australian or New Zealand citizens. |

Source: ABS, 3412.0 – Migration, Australia, 2016-17

So, a policy reducing overseas migration necessarily means a cut to one of the following groups;

Temporary migrants: Students

‘Higher education’ (30%), ‘Student other’ (12%) and ‘Vocational education and training sector (1%)’, collectively accounted for 43% of NOM in 2017

The impact of cutting visas for students and higher education? Students are worth $31.1 billion to the Australian economy.

Temporary migrants: Backpackers

‘Working holiday’ visas accounted for 11% of NOM in 2017

We changed the rules a few years ago to allow backpackers to stay longer than a year, provided they spend some time in regional areas.

With the agricultural sector already struggling to fill job opportunities in regional areas, they will feel the impact of any cut to NOM that would reduce the number of backpackers coming to Australia each year.

Temporary migrants – 457 Visa holders

‘Temporary work skilled (subclass 457)’ visas accounted for 6% of NOM in 2017

The business community, particularly those in the growing technology sector, are hungry for skilled labour, and protest whenever there are restrictions placed on skilled migration programs such as 457 Visas.

Permanent migrants – Family reunions

‘Family’ visas accounted for 9% of NOM in 2017

You’re an Australian, you’ve moved overseas, and you’ve married a citizen of another country. You want them to move home to live with you in Australia? Apply here.

But we’re talking about Australian population, not temporary visitors?

If we’re talking about ‘population growth’ or ‘population pressure’, it begs the question – who is counted in the Australian population?

By the standard United Nations definition (which Australia adheres to), a person is counted in the population of a country if they have been here for 12 months of a given 16-month period.

So, a British backpacker who is travelling around Australia, picking fruit, waiting tables and living it up from The Sunshine Coast to St Kilda – as long as they’re here for twelve out of their sixteen-month gap ‘year’, they’re counted in the Australian population.

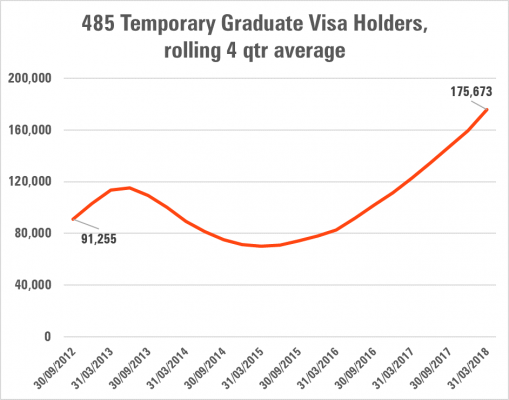

Students staying on

As shown above, students accounted for 43% of the temporary migration to Australia in 2017.

While the government don’t publish their assumptions about how the different categories of migration relate the forecast NOM figure, one thing that might explain the continuation of a high NOM figure is ‘people staying around’.

In other words, if government policy limits new arrivals, but migrants who came in recent years remain in Australia (ie. ‘NOM departures’ are low), the net effect is that NOM remains high.

In a recent presentation, Keenan Jackson, a consultant in our economics team, showed the growth of students on the 485 temporary graduate visa.

Source: Department of Home Affairs, 2018

This visa allows ‘international students who have recently graduated with skills and qualifications that are relevant to specific occupations in Australia’ to live, study and work in Australia temporarily.

So, while this isn’t a permanent visa, it does give students the right to stay on while they’re looking for work, extending the time they spend in Australia.

Separately, a 2015 study showed that 90% of international students were employed three years after graduating, with almost 40% living in Australia.

So, who gets the chop?

As you can see, a cut to permanent migration necessarily translates to a cut in one of the above categories. And a reduction in places for any of these categories will directly impact our domestic economy or, in the case of family or humanitarian visas (6% of NOM in 2017), the benefits and societal standards our citizens enjoy and uphold.

Learn more about what’s driving our population growth

If you’re interested in this subject, subscribe to our blog here and stay tuned.

Glenn has been writing a terrific series about the components of population change, so you can understand what is really behind the growth in Australia’s population.

*Correction regarding ‘Visitors‘: the original version of this blog said ‘Net overseas migration from ‘Visitors’ accounted for 22% of total NOM in 2017, but as they’re mostly here for less than 12 months, they’re not counted toward population’. Thanks to Henry Sherrell for the clarification below:

The “Visitors” currently defined in the 3412.0 ABS Migration series is explained by the following. The ABS only tracks a person’s first visa and not any transition after arrival. So when a person turns up on a tourist/visitor visa but then moves to a student, work or family visa, they show up in the NOM and population statistics as a ‘visitor’. Currently, there are longer waiting periods for various visas, which is driving this phenomenon of additional ‘visitors’ in the population.