As most Australians are well aware, the 2016 Census didn’t go exactly as planned. There was a major DDOS attack on August 9th causing the ABS website to fail, right when everyone was being encouraged to do their Census form online. And to make it worse, the ABS didn’t even deliver paper forms to most households so there was no easy fallback. The Census website was down for nearly 2 days around the peak time when most people would have filled in their Census. And there were continued discussions about the ABS privacy policy, the name and address retention and data linking projects, which some people saw as an invasion of privacy. Government ministers got involved in what is usually not a political process, and many people were even calling for the Census to be cancelled. The #Censusfail hashtag gained momentum and there was a major Senate enquiry into the running of the 2016 Census.

Despite all this, the Census went ahead, and collection of the responses continued up until the end of September last year. We have now received the first results from the 2016 Census, with the bulk of datasets at all levels of geography released by ABS. They also released the findings of the committee into the data quality, and details of the undercount (how many people were missed).

So how did the Census do? Are the data reliable?

For the 2016 Census, the ABS appointed a “Census Independent Assurance Panel” to oversee the release of Census data. They released their report on data quality today, and you can read it here.

There’s a lot in there, and I haven’t read it all yet, but the upshot is that “In summary, the Panel has determined that the 2016 Census data is of a comparable quality to previous Censuses, is useful and useable, and will support the same variety of uses of Census data as was the case for previous Censuses.”

i.e. The data’s OK!

The undercount

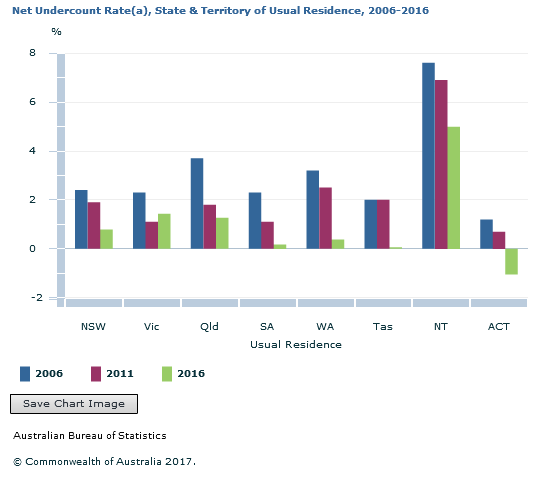

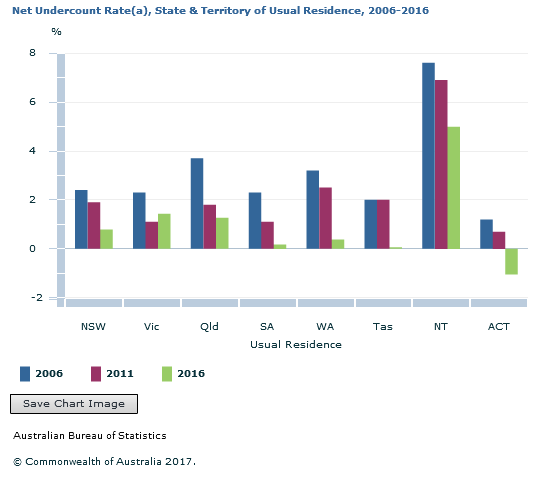

The Post Enumeration Survey estimates how many people were missed or double counted in the Census. This shows for 2016, a “net undercount” of 1.0% of the population – i.e. about 1% less people were counted in this Census than should have been.

This varies from state to state, with the interesting point that, while the undercount overall decreased, in Victoria it increased, and the largest number of missing people were in Victoria. And the ACT had a net overcount – they must be so keen to fill in their Census forms in Canberra quite a few of them did it twice!

View the net undercount chart in its original form here.

Who was missed?

There is a fascinating chart, which shows that you’re more likely to be missed in the Census if you’re a young child or a 20-something, while if you’re over 50 you’re more likely to be double counted.

While there were a number of dwellings which did not complete a Census, the actual “item non-response” – where a respondent has left a question blank – was down to 1.8%, from 2.4% in 2011. So more people are answering all the questions.

Overall, the data looks quite good. However, this is NET undercount, and delving a bit deeper into the figures, we see there are some areas where the 2016 Census response rate is not as good as previous Censuses.

For instance, the actual dwelling response rate in 2016 was 95.1%, down from 96.5% in 2011 (section 3.3.2 in the report). This is the actual number of dwellings thought to be occupied on Census night who actually returned a form. And the equivalent “Person response rate” is 94.8%, down from 96.5% in 2016. This is likely to be directly attributable to the website being down on Census night and the longer lead-time for collection, meaning people had moved houses etc. The difference between the two figures is that some people are overcounted, which is why we call it a NET undercount rate.

So while the Post Enumeration Survey estimates that 4.3% of people were missed in the Census, there were also 1.3% who were overcounted (counted more than once), leading to a net undercount of persons of 3.0% (Census Independent Panel Report, Table 3.2.2).

The overall figure of 1.0% net undercount includes another factor, which is people imputed into dwellings. All those dwellings which didn’t return a form but were thought to be occupied on Census night had people imputed to them, and the Post Enumeration Survey estimates that there were TOO MANY imputed into them this time around – some counted elsewhere already for example. This net overcount is estimated at 2.0%, which is subtracted from the total of 3.0% to produce the final undercount figure of 1.0%. So while the population counts are pretty good, we don’t have any information on most of the characteristics of those people who were missed.

This all gets very technical, and you can read the report for further details.

Overall data quality

The key take-away is that, although the Census data are broadly comparable to previous years, and certainly very useful for a wide range of purposes, the issues which affected the Census collection have had a minor impact on the data. Due to difficulty contacting all dwellings, there is a slightly lower rate of people with their data in the Census record file. It’s still around 95% complete, and the various mechanisms such as imputation and the Post Enumeration Survey ensure that we get the population right.

Every Census has its issues, and the 2016 Census seemed to have more than most. However, in light of what happened at the time, this is still a pretty good result, and shouldn’t affect the use of the data in most cases.

We are busy rolling out the new Census data to all our clients over the next month. Stay tuned for updates on when this is going live.

.id is a team of population experts who combine online tools and consulting services to help local governments and organisations decide where and when to locate their facilities and services, to meet the needs of changing populations.

Access our free demographic resources and tools here