In our last post, we noted that while Australian population growth is projected to slow towards the end of this century, Australia will still ‘outgrow’ much of the world, including many of our major trading partners (Chart 1.)

Chart 1. Trading Partner Population Growth (2010=100)

Source: U.N Population Projections

Why is that the case? How is it that Australia will find itself growing faster (in percentage terms) than almost all developed economies?

One of the key factors, and one often overlooked, is the role immigration plays in shaping our demographic future.

Many Australians would probably be surprised to learn that Australia is, in the scheme of things, a high-immigration country. We currently have one of the highest net overseas migration rates in the developed world (Chart 2).

Chart 2. Immigration Rates, Select Countries (net overseas migration, per 1,000 people)

Source: C.I.A World Book

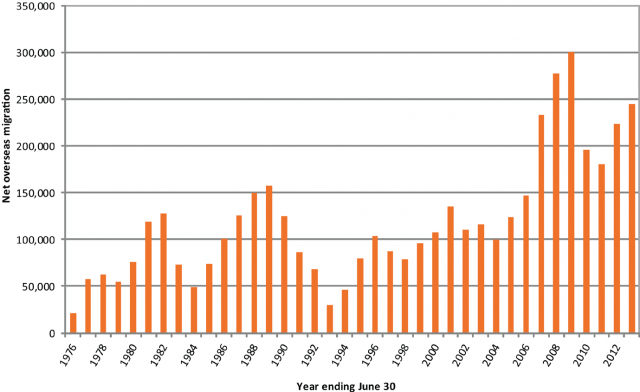

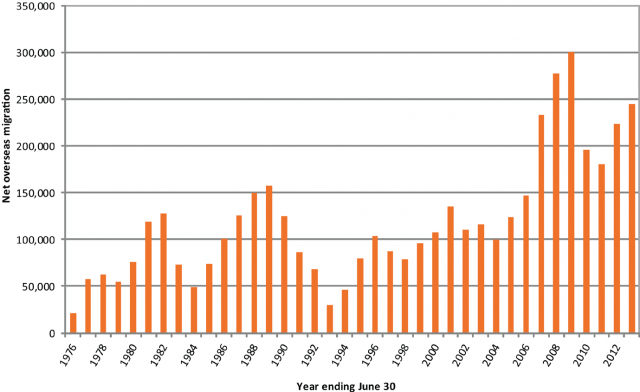

However, our immigration intake is currently much higher than historical averages. Chart 3 tracks Australian net overseas migration from 1976-2013. The first point to note is that immigration typically moves with the business cycle. That is, immigration rises during the good times, and falls during recessions (e.g note the lows around 1983 and 1994.)

Chart 3. Net Overseas Migration – Australia

Source: ABS, Australian Demographic Statistics

The other point to note is that there’s been a level shift in our immigration intake, beginning around 2006. It rose to a peak of 300,000 persons in 2009, and though it fell slightly after the GFC, it has continued to hold around the 200,000 persons mark. In 2013, it was just shy of 250,000.

When you remember that in the 25 years leading up to the new millennium the average intake was somewhere around 50 to 100,000 persons, you get a sense for how significant this structural shift in our immigration rate has been.

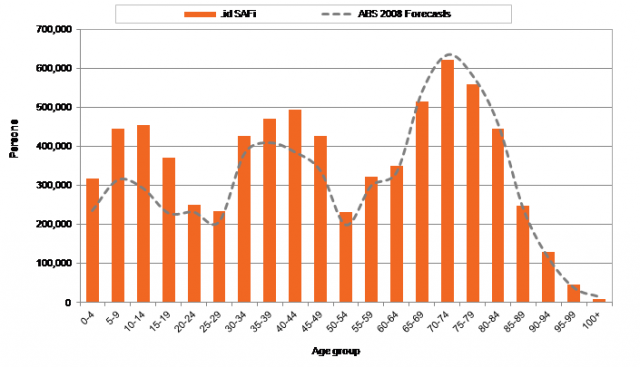

This change is also reflected in official population projections. In 2008, the ABS assumed an immigration intake of 180,000 in their central scenario. That has now been revised up substantially to 240,000 . There have been similar revisions to Victorian State Government projections.

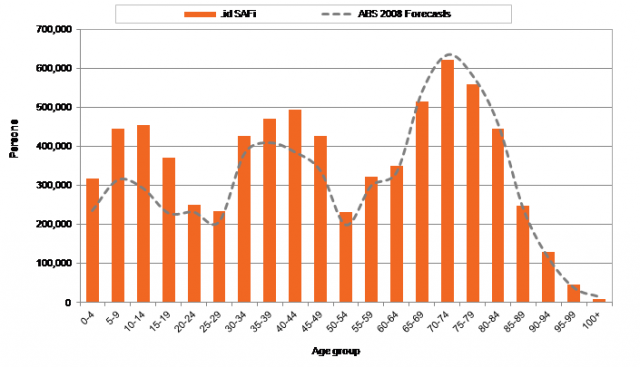

So how much impact do these different immigration assumptions have on future population outcomes? In Chart 4 we compare the 2008 ABS forecasts with an overseas migration assumption of 180,000, to .id SAFi forecasts with an assumed migration of 200,000 persons.

Chart 4. Forecast Comparison – Australian population growth by age

Source: ABS, Population Projections, Australia, 2006 to 2101; .id SAFi

When you present the data in this way, it becomes clear that immigration doesn’t just affect the overall size of the population, but also its composition by age.

Migrants to Australia undergo a strict vetting process – we are typically looking for young, skilled people to enter the country and contribute to our workforce and economy. For this reason, the age of migrants tends to be much younger than the population overall.

This in turn influences the Australian fertility rate. If our immigration program focuses on young, but professionally established people, then we are implicitly focusing on people coming around to that stage in life where they are getting ready to have children.

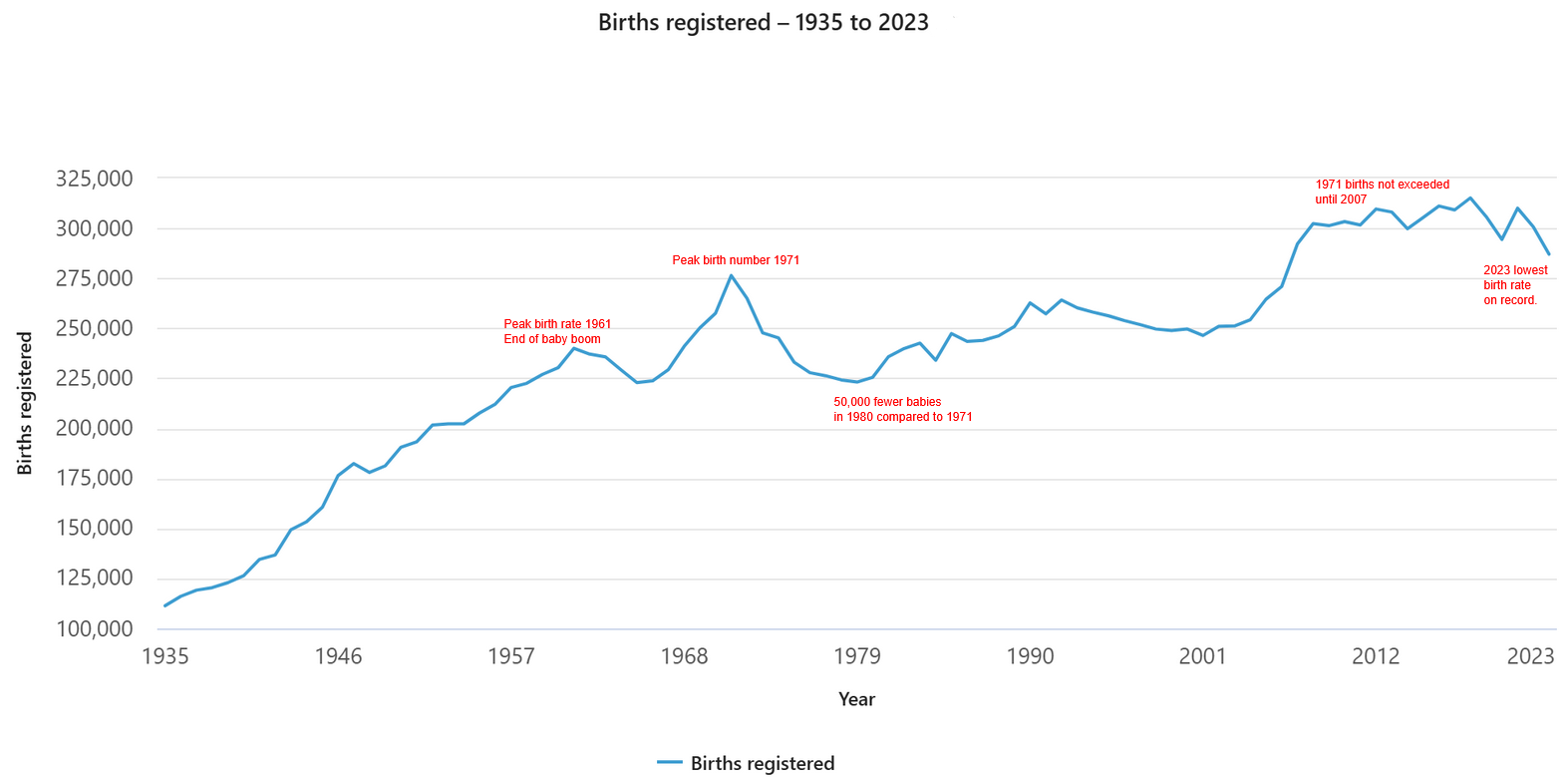

Indeed, we have seen a marked improvement in the Australian fertility rate in recent years. Our immigration program has undoubtedly contributed to that, though the influence of shifting cultural norms and preferences should not be underestimated either.

The net effect of improving fertility rates and a strong immigration program is a more balanced population profile. Despite the focus on baby-boomers in recent years, the ageing of society will be much more harshly felt in other parts of the world, including Japan, China and much of Europe. Australia finds itself relatively well positioned.

We explore the challenges and opportunities that the shifting demographic structure of Australian society presents further in our free ebook Three Growth Markets in Australia. This is an excellent resource if you’re looking to understand how key consumer markets will evolve over the next 30 to 50 years.