The last remaining seat in the recent Victorian State election has finally been decided, almost two weeks after polling day. The lower house seat of Prahran in the inner south-east of Melbourne has been claimed by the Greens, after a very tight contest which saw the Greens finish third on primary behind the Liberal and Labor candidates. Politics aside, what can the built form of the area tell us about the cause of this surprise election result?

The seat of Prahran is the state’s smallest at just 11.9 square kilometres, and the reason this tiny electorate can display such diverse political aspirations can be traced back to the development of the area from the early days of European settlement.

The topography of the area (which includes the suburbs of South Yarra, Prahran, Windsor, and parts of Toorak, St Kilda and St Kilda East) was a primary influence in determining the original pattern of urban development. Permanent settlement began in the 1840s on the high land closest to the main Melbourne settlement, between the Yarra River and what is now Toorak Road. These more elevated, well-drained areas of South Yarra and Toorak were the most attractive, and were occupied by people of a higher social status than those who moved onto the lower lying, flood-prone areas of Prahran.

The slightly higher ground to the south-west became the suburban area of Windsor, and again was more attractive due to its elevation and proximity to the fashionable seaport of St Kilda. The central area of Prahran was referred to in the early days as a swamp and was traditionally a working class area, with many of its residents providing labour and services to their wealthier neighbours on the surrounding higher ground.

These more affluent areas featured large houses built on extensive lots, while the poorer areas were quickly subdivided into much smaller lots with more densely packed dwellings, and so the early pattern of land use was established. This generally persisted throughout the gold boom of the 1850s and the land boom of the 1880s. However, the subsequent land bust of the 1890s and the Great Depression of the interwar years saw many of the large estates either partially or completely sold, freeing up large sites suitable for the development of higher density ‘mansion’ style flats which are still such a feature of the area.

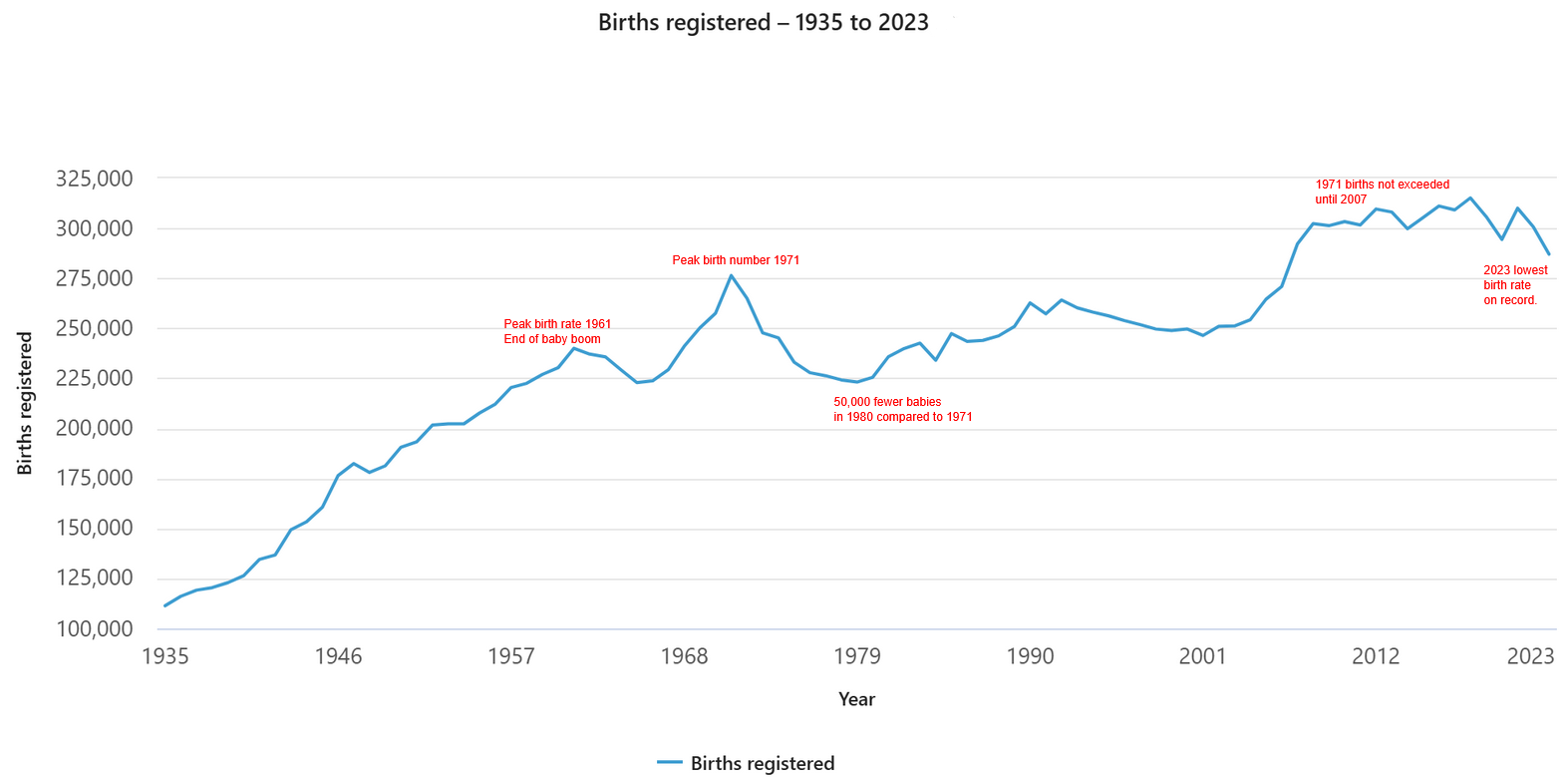

The lower lying parts of Prahran with the smaller established subdivisions offered less opportunity for large infill flat and apartment developments, and the focus between 1920 and 1950 was more on the repair of run-down buildings than on new development. The post war baby boom of the late 1940s and 1950s promoted a focus on home and family, and with the growing dominance of the motor car, many people aspired to bring up their families in the newer outer suburbs away from the grime and overcrowding of the inner city. The population of Prahran, like that of many inner suburbs, declined significantly. As a consequence, housing costs tended to fall and some of the working-class people who moved out of western and central Prahran were replaced by new migrants from overseas, particularly Europe.

The government response to the issue of population decline was to advocate for higher density housing, particularly flats, and as a result the 1950s and 1960s saw the building of many new developments, both private and public. This building boom coincided with another demographic shift towards smaller households, and many of the people who wanted to move into the new flats were either young and single, or retired.

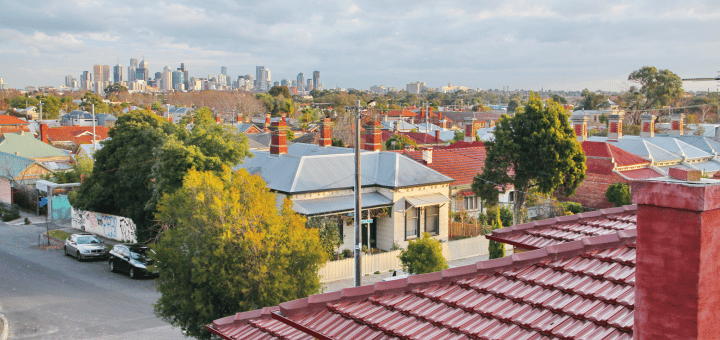

More recently, the residents of Prahran have come to increasingly appreciate the charm and appeal of the older housing, and many original homes have been lovingly restored and the area gentrified, with more young families either remaining or moving into the area. The trend towards densification has continued with the many new flats and apartments built in the precincts close to public transport and other amenities attracting young professionals often without traditional political allegiances, enabling the rise of support for alternative parties such as the Greens. The area now has an extremely eclectic mix of dwellings from the remaining original large mansions, to small Victorian cottages, and newer high density flats, apartments and townhouses.

It is this diversity of social and physical infrastructure that paved the way for the intriguing three-way contest played out at the recent election. Whilst it appears the Greens have triumphed at this particular point in time, undoubtedly this diversity will reassert its influence at the next election, at which time the result could easily be very different. The only certain thing is that the electorate of Prahran is likely to remain as unpredictable as it is diverse.