Recently the National Seachange Taskforce released a report about the impact of temporary populations in coastal areas. Central to the report was a survey of non-resident ratepayers, and whether they intend to move to their coastal property in the future. While the report provides some valuable insights into the reasons and motivations behind population change in coastal locations, we know that recent population data shows that growth in coastal areas might be slowing down. The report concludes that 30% of holiday home owners intend to move to their coastal property in the future. But intriguingly, there is no mention of out-migration from coastal areas, which of course is the other side of the migration equation.

Internal migration

The way people move around Australia (internal migration) is an important component in determining how populations change. The difference between people moving in and those moving out is net migration. It is the net migration that is the critical element here – if more people are moving into an area than moving out, then it is recording net in-migration. The Australian Census contains two questions that provide an indication of the extent of internal migration – where did you live one year ago and five years ago? The data collected through this means provides valuable insights into the patterns and directions of moves that is not really available from other publicly available data sources. Importantly, it is possible to ascribe age – at least into a five year cohort. There is a strong relationship between age and migration, with young adults being the most mobile age cohort. At .id we demonstrate by way of age specific migration over time to show councils which age groups are contributing to population change in their local area. It’s a simple but effective method.

The example of East Gippsland Shire

East Gippsland Shire is located in the far east of Victoria. Much of the Shire consists of rugged terrain and national parks, with settlement largely confined to the coastal strip. Agriculture and food production are important around Bairnsdale (the regional centre), and coastal towns have long been popular holiday and retirement destinations. There are a large number of holiday/second homes in towns such as Paynesville and Lakes Entrance. It does not fall into Melbourne’s commuting catchment so this is not a driver for growth, but the population has grown consistently over the last 20 years and reached 43,103 in 2012. In 2011, about one in five dwellings were unoccupied on Census night, and this proportion has remained fairly constant since 1991 (if anything it has increased slightly).

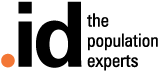

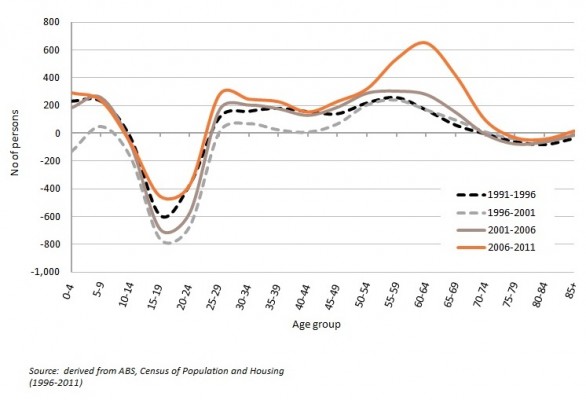

The age specific migration chart for East Gippsland, covering the last four Censuses, is shown below. Positive values indicate net in-migration (more people moving in), and negative values the reverse (people moving out). Over time the pattern is remarkably consistent – East Gippsland gains young families ie 25-39 year olds and their children aged 0-9 years, as well as retirees (generally aged 55-69 years). In fact, the latest intercensal period indicates an increase in retirement migration gain.

The chart is equally revealing in indicating who is moving out. Like most of regional Australia, East Gippsland loses young adults (primarily aged 18-24 years), who move elsewhere for employment and education purposes. This report confirms some of the long held assumptions around the reasons for young adults moving out of country areas. There is also a slight loss of elderly persons which is more of a reflection of a move into a non-private dwelling such as a nursing home – a quirk of the way we compile this chart. However in some areas it can indicate out migration – there is little qualitative evidence on the reasons why elderly people may move away from a coastal area, but anecdotal evidence suggests that it may relate to feelings of isolation eg distance to family and services.

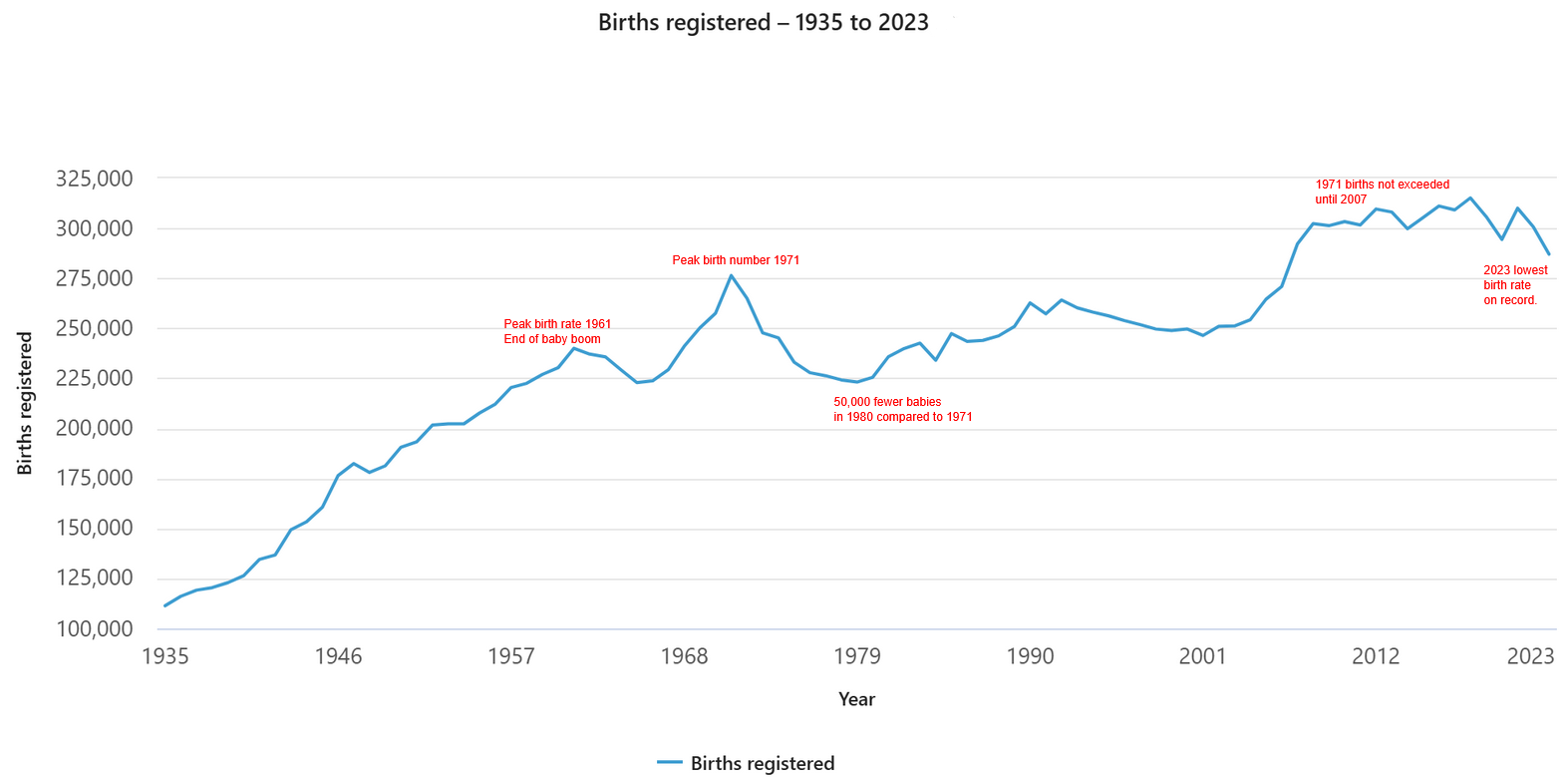

Almost one in three respondents in the National Seachange Taskforce report indicated that they intended to move to their coastal property at some point in the future. Significantly, but not surprisingly, the majority of these are “baby boomers” ie 45-64 year olds. On the face of it, this appears to indicate that there is likely to be a significant wave of migration to coastal areas in the future. But this result needs to be considered in the wider demographic context total migration in and out of an area, not just those who may move in. Furthermore, back in the pre-Cambrian era yours truly studied these migration patterns to the south coast of NSW as part of her Honours thesis. Owning a holiday home, or buying a new house on the coast and moving into it post retirement has been part of the demographic story for some decades now.

Temporary populations and forecast.id

The National Seachange Taskforce report does correctly emphasise one of the challenges facing coastal councils in terms of measuring populations, and how this is incorporated into funding models. There is a mismatch between the population as measured by the usual residence count in the Census, and the peak population measured over the December/January period in particular. The report makes an attempt to determine the extent of the “missing” population that the Census does not count. The results are quite compelling and provide an insight into the challenges faced by coastal councils in providing services, not only for their permanent populations, but for the larger population that impacts greatly in a small window of time.

The report emphasises that the Census needs to be maintained as the “gold standard” in measuring populations, but that these alternative population measures need greater prominence in official population statistics. This is the key issue – the ERP is the official measure of population in Australia and it is the evidence base for our population forecasts. Though the results of surveys on migration, and attempts to measure temporary populations are insightful, it remains a key part of .id’s forecasting methodology that we use the 2011 ERP as the starting point. We also consider other available evidence such as building approvals to place demographic trends in context. Now that the ERP has been rebased to incorporate the results of the 2011 Census we have a new basis upon which to prepare forecasts for the period 2011-2036. The forecasting team has begun preparing forecasts using this data and we will be progressively updating these for our clients over the next 18-24 months.

Access forecast.id at our online demographic resource centre now! Our forecast.id websites are being progressively updated with 2011 Census data. Register here to get the latest Census updates.