I recently wrote a blog where I made the point that the largest group attracted to greenfield developments in growth areas were younger families with parents typically aged 20-34 years. This prompted queries about the mix of housing achieved within newly developing areas.

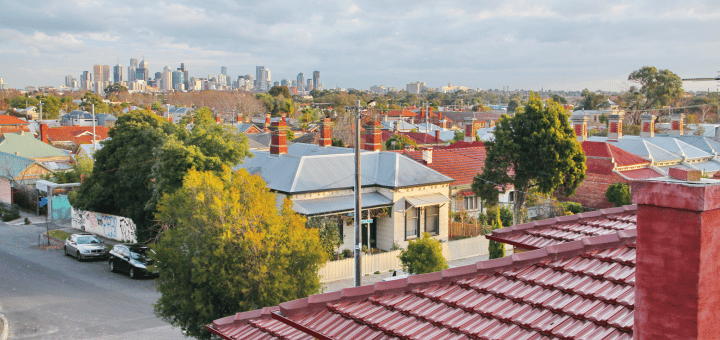

A typical greenfield housing estate

Most new suburbs have a fairly homogenous type of housing product, aimed at younger families. In many estates, most lots range from 450m² to 700m², often with a net dwelling density of 10-15 dwellings per hectare. To put this in perspective, the type of family housing found in much older suburbs within Melbourne and Sydney have a large stock of separate dwellings on 200-400m, or roughly 25-50 dwellings per hectare (the typical “single front” house). Townhouses, typically, can be expected to equate to roughly 75 dwellings per hectare.

A typical new estate – Newhaven Estate Plan, Piara Waters

What about medium density housing?

Most new estates are likely to have some smaller medium-density townhouse or attached dwellings, within designated medium density precincts; but the focus here is not so much on diversity as affordability and such dwellings are generally marketed as start-up homes to a similar young family demographic. Another class of medium-density housing which can be found in newly developing areas is the retirement village, which is likely to contain smaller units; however, these dwellings are restricted to retirees, form a very small proportion of the overall dwelling stock and are generally developed by specific bodies whose business is the management of such estates.

Can housing diversity be achieved in new estates?

Housing diversity in new growth areas is a little bit of a chicken and egg argument: if there is little diversity in housing type, then you are unlikely to attract different markets into new growth areas; however, if there is little evidence of a market for higher or medium density housing within the growth areas, then developers are unlikely to provide alternative housing formats.

There are some very real disincentives to providing a diverse housing supply within greenfield areas. Firstly, higher density developments involve a lot of investment and present significant risk to developers and financiers whereas family type housing has a proven track record and represents more of a safe bet.

Higher density developments are often targeted at investors, looking for ongoing rental income, and therefore require a ready supply of people who wish to rent. Young adults are the largest demographic attracted to rental housing, looking to be close to employment or education opportunities, and thus higher density formats are generally concentrated within the inner city, or around employment centres and are unlikely to be attracted out to newly developing areas, which by necessity, are on the city fringe.

The demographics likely to be attracted into alternative forms of housing are relatively footloose, and have considerable choice as to the area or suburb they wish to live in. Similarly, older people, wishing to downsize, also have a wide choice – whether they wish to retire to a coast, the country, a retirement community or the inner city. Young families, however, are looking for affordable larger type houses, with space being a premium, and it is this type of product that growth areas can produce.

There may be a market for some young families to purchase higher density “family-type” apartments, but this market is unlikely to be attracted to new developing areas, but rather into inner city areas with high amenity. The argument for such dwelling stock in greenfield areas begs the question as to why families would decide to live within an apartment, when there is a plentiful supply of relatively affordable houses being developed close by?

Where has more diverse housing been achieved on the fringe?

There are examples where a diverse housing stock has been achieved within new development areas; however, these tend to be around “masterplanned” centres, which have considerable government agency involvement and are often publicly subsidised with significant infrastructure provision.

Rouse Hill, Sydney

One example is the Rouse Hill Town Centre, in the Hills Shire, Sydney, which contains apartment developments. Landcom, a government agency, has been involved in its development and, of course, there has been the long promised North-West rail link which will service Rouse Hill and some of the neighbouring suburbs.

Cockburn, Perth

Cockburn Central in City of Cockburn, southern Perth has achieved considerable densities; however, again this is a planned regional centre with the Western Australian Planning Commission providing rail infrastructure and significant development by LandCorp, the government agency responsible for delivering land and infrastructure projects in Western Australia.

Cockburn Central, Perth, WA

Joondalup, Perth

Another good case study is the City of Joondalup, again in Western Australia. Joondalup formed as a planned community, and the central business district has been recently developed with a diverse housing stock, including higher density development; but this has happened as a result of considerable infrastructure development – the rail link, significant tertiary education institutions and the development of industrial and commercial centres, providing considerable employment opportunities. Without the development of infrastructure in terms of transport and employment, it is unlikely that a newly developed area will be able to attract the type of market that would be support a more diverse housing product.

Joondalup Town Centre, Perth, WA

Understanding the changing role and function of greenfield areas

Arguably, it is not the role of most greenfield areas to produce diverse housing, but instead to produce the affordable “family-type” house desired by young families, a large proportion of whom are unable or unwilling to purchase such a house within the older suburbs.

The opportunity to provide a diverse housing stock is not during the initial phase of development, but is only likely be a realistic proposition once the area has become established and young families initially attracted to the area have aged. At this point in a suburb’s life-cycle, people who moved in as children have grown up and are beginning to leave home and there may be a proportion who wish to remain within the area, and are looking for affordable alternatives; alternatively, older people whose children have left home may be looking to downsize whilst retaining their ties to the area, and may be attracted to medium density type dwellings.

Flexible urban design is the key

The best way to ensure future diversity within today’s growth areas is to provide for flexibility in the urban design and subdivision pattern of newly developing areas. Housing lots of greater than 600m², based along streets organised on a grid pattern, allow for future subdivision and diversity as demand develops, whereas smaller lots and street patterns based around cul-de-sacs (popular on estates developed in the 1980s and 90s) present significant barriers to redevelopment and future housing diversity.

If you would like to receive more updates about demographic or economic trends, do follow us on twitter @dotid or subscribe to our blog (above). You may also like to visit us at id.com.au where you can access our demographic resource centre.