In light of the current controversy over the inclusion of a citizenship question in the 2020 US Census, Glenn points out a citizenship question has been part of the Australian Census since 1911, and, using this data, lists the LGAs in Australia with the highest and the lowest proportion of Australian citizens.

I was reading about the current debate in the USA about putting a question on US citizenship in their Census. The US has a Census every 10 years, with the next one due in 2020, and the Trump administration wants to put a question on citizenship in, for the first time in 70 years.

Apparently it is quite political, with suggestions the results might be used to adjust electoral boundaries to favour one side or the other. There are also concerns that putting such a question on the Census might increase the number of people not willing to respond to the whole Census, therefore increasing the undercount and usefulness of the Census more generally. This is often a concern when adding a question which might be considered sensitive – it could put people off answering at all.

This article gives a useful summary of the debate. I really don’t want to get into the politics of it, but I have to say I was a bit surprised that it would be so contentious. I guess it might be different in a country with large numbers of illegal immigrants, or perhaps it is a difference between our compulsory voting and the optional voting they have in the US. It’s also worth mentioning that the US Census is very short, with just 10 questions – compared to Australia’s 60 or so – But on the Australian Census, we’ve had a question on Citizenship or Nationality on every Census since 1911, and it has appeared in its current simple form since 1986.

The Census question on citizenship is not used to define a person’s ability to vote (apart from anything else, Census individual responses are completely confidential, and not related to the electoral roll), though it’s certainly a good proxy and is used as an input to the population model used to define electoral boundaries in Australia. More information on that process can be found on the AEC site.

I’d have to say the citizenship question is probably one of the least contentious Census questions we have, which is why the US debate surprised me a bit. I’ve never heard it referred to as an invasion of privacy or any objections to it being on the form.

It’s probably not one of the most heavily used topics among .id’s clients – Local Governments do host citizenship ceremonies, but for the most part, whether or not a population are citizens or not won’t affect the services provided at a local level very much.

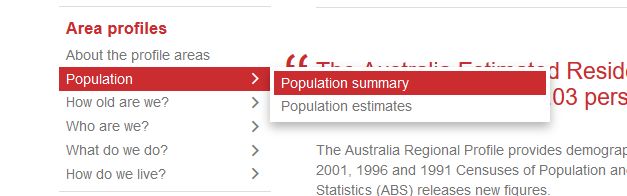

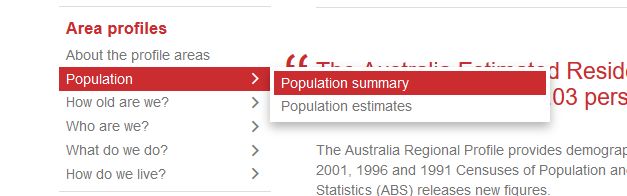

How we show citizenship data

So on profile.id – our flagship Census profile – we don’t have a separate topic page for Citizenship – in fact, we put it as a couple of items in our key statistics page, found under the “Population” heading.

There are two items in there for each LGA, suburb and town.

- “Australian Citizens”

- “Eligible Voters (citizens aged 18+)

The Eligible Voters category is not going to be an exact match to the electoral roll, because not everyone is enrolled to vote, and there are also some differences (eg. prisoners serving a term of 5 years or more are not eligible to vote, and British subjects who arrived before 1984 are eligible to vote even if not Australian citizens). But it’s a good proxy.

So what proportion of people are Australian citizens?

Here’s how it’s changed over time, for the past 6 Censuses.

| Census year |

Citizens |

Eligible voters (citizens aged 18+) |

| 1991 |

85.9% |

61.9% |

| 1996 |

89.5% |

65.5% |

| 2001 |

88.2% |

65.6% |

| 2006 |

86.1% |

64.8% |

| 2011 |

84.9% |

64.5% |

| 2016 |

82.4% |

62.8% |

At a national level, it’s fairly steady. It’s impacted a bit by changing response rates over time, but also the proportion of citizens nationwide has declined the last 4 Censuses, which coincide with an upsurge in migration which started around 2006. So generally if there are more recent migrants, you will have less Australian citizens.

This checks out when you look at the areas with the highest and lowest proportions of citizens too. The highest rates are in mainly Australian-born populations, in regional and remote areas and particularly aboriginal communities – the lowest being in the most multicultural parts of our capital cities – particularly Sydney and Melbourne.

Highest percentages of Australian citizens (LGAs with > 1,000 people, citizens as a % of all persons who stated an answer to the question)

| Yarrabah (Qld) |

100.0% |

| Cherbourg (Qld) |

99.5% |

| Palm Island (Qld) |

99.3% |

| East Arnhem (NT) |

99.1% |

| West Daly (NT) |

99.1% |

| Doomadgee (Qld) |

99.0% |

| Aurukun (NT) |

98.9% |

| Anangu Pitjantjatjara (SA) |

98.7% |

| Coolamon (NSW) |

98.7% |

| Coonamble (NSW) |

98.7% |

Lowest percentages of Autralian citizens (LGAs with > 1,000 people, citizens as a % of all persons who stated an answer to the question)

| Melbourne (Vic) |

51.3% |

| Perth (WA) |

56.8% |

| Adelaide (SA) |

63.9% |

| Sydney (NSW) |

64.4% |

| Burwood (NSW) |

68.2% |

| Strathfield (NSW) |

71.1% |

| Canning (WA) |

73.3% |

| Greater Dandenong (Vic) |

75.2% |

| Monash (Vic) |

75.3% |

| Parramatta (NSW) |

75.5% |

So in summary, this information is used by the electoral commission and is an interesting, different way of looking at cultural diversity – it really varies by the proportion of recent immigrants in an area. But generally, it’s an integral part of our Census and just doesn’t generate the controversy that it seems to be creating at the moment in the USA.