Over a coffee, a mate was recently mulling over her lot as a widowed woman close to retirement age. Apart from the amusing tales she had to tell of rejoining the dating game after a 40 year sabbatical, this 65ish lady talked about living alone and finding herself in a classic empty nest scenario, rattling around in a big family home.

My mate commented that it was a shame older people seemed less likely to consider flatting or some sort of communal cohabitation. She felt living alone was possibly an isolated, lonely existence, though when contemplating the ‘flatting’ alternatives she admitted that recent dating experiences had highlighted her intolerances.

My immediate response was to agree. Intuitively single-person households seemed to be more socially vulnerable and I thought that people living on their own might be less happy than those in bigger households. On a wider scale I thought that a high proportion of single person households would lessen community connectedness and cohesion.

Yet I had a niggling feeling that my perceptions might be a bit half-baked and as a researcher felt driven to … well … research.

Turned out that there was a lot of international research to contradict my perceptions of the lonely single person household. Some studies found there was no difference between single person household and any other household when considering social relations and sociability in general, and most people living in single person household were quite satisfied with their situation. Other researchers argued that communities with higher proportions of single person households had lower levels of social capital.

However, studies were united that single person households are often vulnerable financially – especially those single person households of older individuals, women in particular. This is because health in the elderly can often be precarious and most at retirement age and onwards experience an income decline along with the general increase in dependence on social benefits. There is also a growing body of research identifying single person households as typically environmentally inefficient.

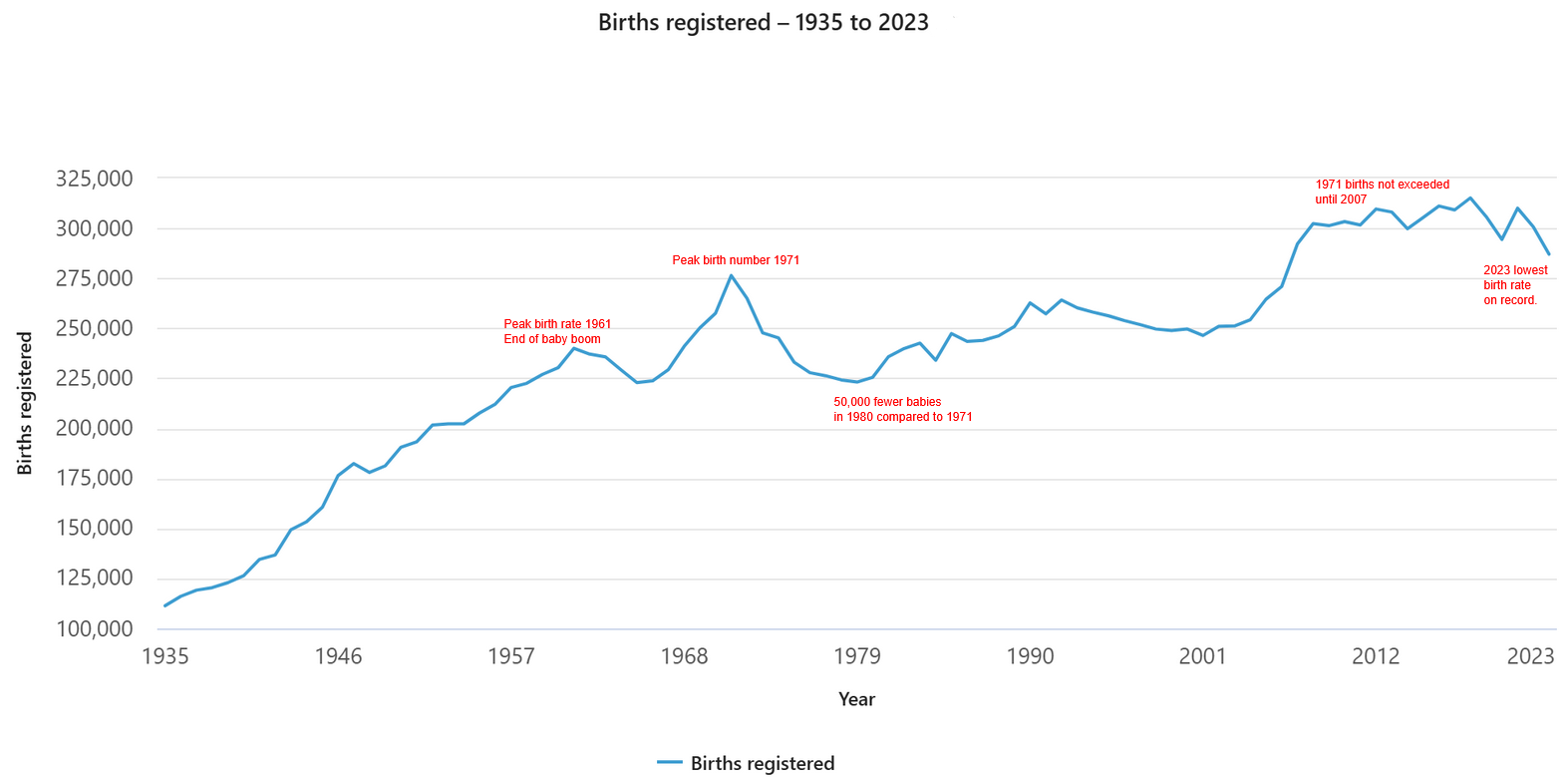

The recent 2013 NZ Census showed that the proportion of single person households has been relatively static over the last decade. Sole person households made up 22.9% of all households in 2013 with a slightly lower figure of 22.6% in 2006. However, the longer term trend reveals rising numbers of single person households, a movement that is projected to continue as a consequence of the populations increasing longevity. And New Zealand will not be the only country to experience the home alone phenomenon.

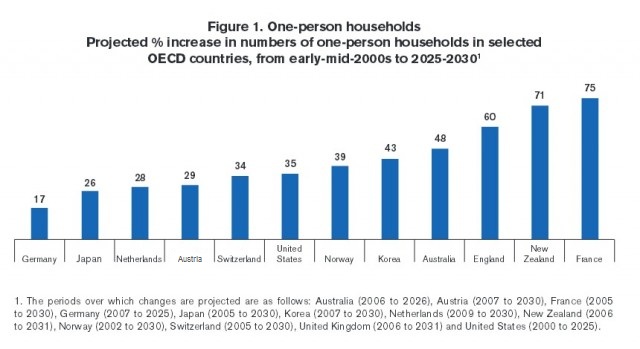

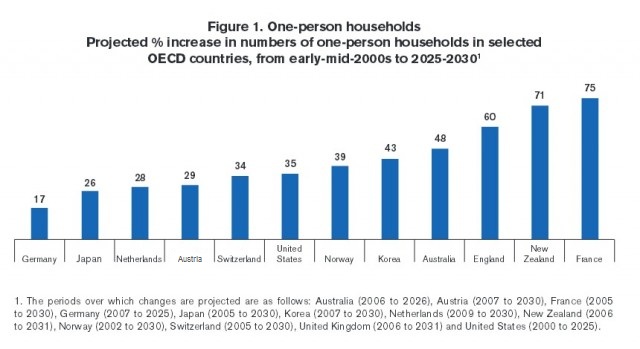

On the international stage the OECD projects a blanket rise in the proportion of single person households as the following table evidences.

Source: OECD (2011) The Future of Families

While the motivations behind a single-person household may vary with some being forced (in the case of divorcees and widowed partners) and some elective, the increases projected are astonishing.

The projected rise of single person households will clearly have an impact across all fields of policy from rating to education, health to housing, transport to recreation.

The speed and magnitude of these projected changes presents a tough challenge for central and local government agencies.

For more information about the future of household types in your area, you can view your .id population forecast on the demographic resource centre. If your Council doesn’t currently subscribe to forecast.id, talk to us – we have solutions for single and multiple council areas.