A recent BRW Article noted that some key business leaders people were taking up arms against ‘Big Australia’.

It reported that Australian entreprenuer Dick Smith was frustrated with a ‘growth at all costs’ economic mindset, and the idea that Australia’s ageing population could be supported through immigration. He said that immigrants themselves grow old, and so such a policy was ultimately nothing more than a “Ponzi scheme”.

At the same time, Flight Centre’s Graham Turner also called for more balanced growth, adding he would like to rein net immigration down from its current level of around 200,000 persons per year, to around 80,000 per year going forward.

For me, the article highlights two things. The first is that the isssue of immigration and population growth is still as provocative as ever, and it remains a hot-button topic on both sides of the policital spectrum.

The other is a slightly misleading focus on absolute numbers. We’d like to suggest an alternative.

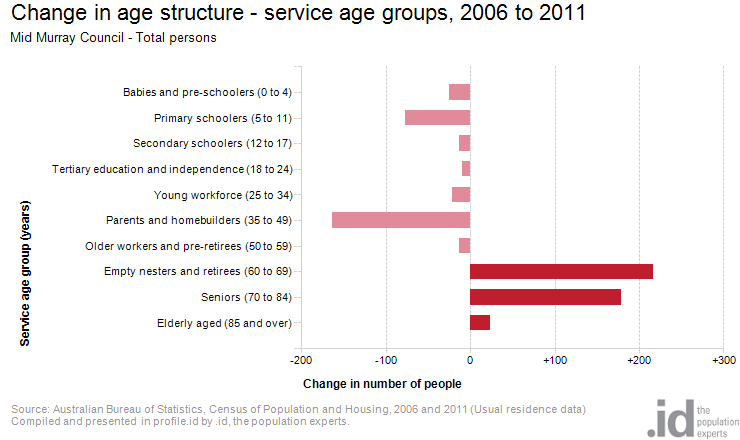

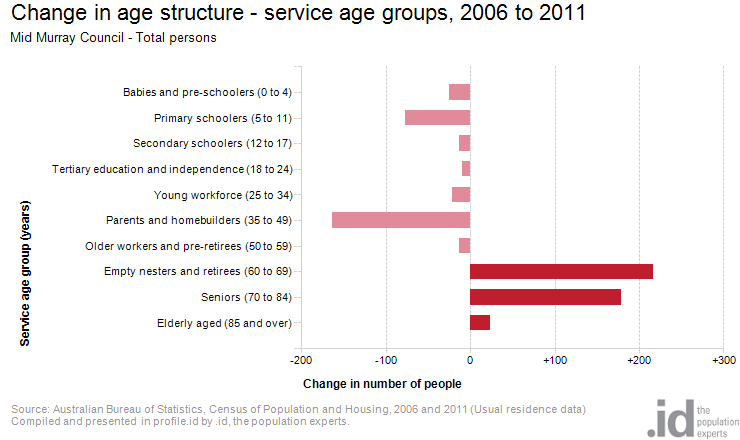

In our last post we highlighted the impact immigration was having on the structure of the Australian population. We compared the ABS 2008 forecasts, which assumed an net overseas migration (NOM) of 180,000 per year, to our own forecasts which assumed a NOM of 200,000 persons (Chart 1).

Chart 1. Forecast Comparison – Australian population growth by age, 2011-2031

Source: ABS, Population Projections, Australia, 2006 to 2101; .id SAFi

As we noted, since immigration tends to focus on younger people approaching child-bearing age, the net effect of increasing immigration is to increase forecasted growth in younger cohorts.

This in turn helps ‘balance’ out Australia’s population profile, with younger groups filling in the gaps left by the baby boomer bulge. This is where the idea that immigration is a ‘solution’ to population ageing comes from. We discuss this in detail in our ebook ‘ Three growth markets in Australia’.

It is legitimate to ask whether a more balanced population profile actually does solve the challenges of ageing Australia, or whether a larger population demands an environmental or social price you’re willing to pay. However, I’d disagree with the assertion that it sets up a Ponzi scheme where we become addicted to more and more immigration.

Generally speaking, the ideal to strive for is balance in the population profile. On the face of it, a higher immigration profile does restore balance. Problems in the profile emerge through sudden lurches – population booms or busts. The baby boomers were a boom. The one-child policy in China was a bust. Both created imbalanced populations and ageing societies.

At .id, we also wonder if it might not be better to think about immigration in percentage terms, rather than in the absolute levels often discussed in the media. If we fix immigration in absolute terms as Graham Turner is suggesting, then over time, as the population grows, immigrants play less and less of a role in Australian society.

If immigration were set relative to the size of the population however, this might create outcomes that were both sensible and politically more ‘sellable’.

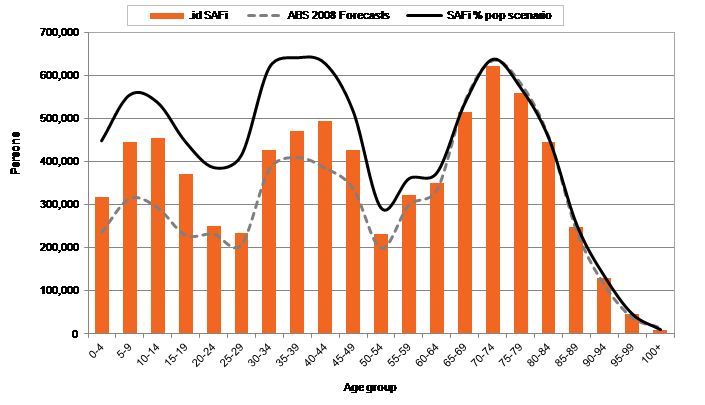

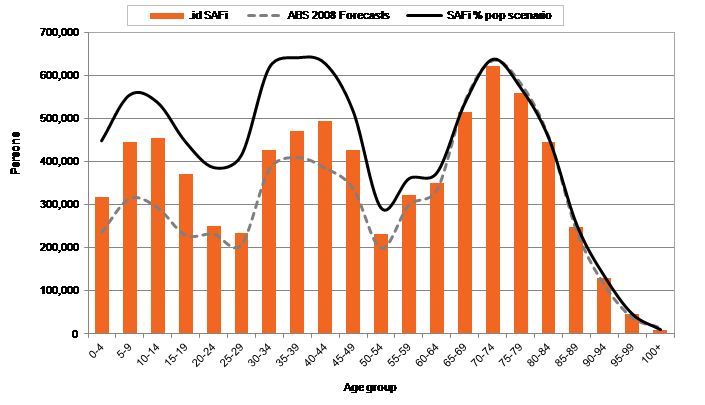

For example, over the 5 years prior to 2013 the net effect of migration has been to add around 1% to the existing population. So if we maintain this relativity throughout the forecast period, we end up with the following result (Chart 2).

Chart 2. Forecast Comparison – Australian population growth by age, 2011-2031

Source: ABS, Population Projections, Australia, 2006 to 2101; .id SAFi

Under this model, NOM goes from 225,000 in 2014 to around 314,000 by 2031. That adds another 1.5 million to the population taking it from an estimated 29.7 million in 2031 to 31.2 million.

Importantly, it goes a lot further to balancing out Australia’s aged profile.

Most importantly, as population forecasters, it’s our job to be realists. In my memory, our immigration program has always had the best interests of the Australian economy at heart. There are only a few exceptions to this rule that I can remember – visas for the Chinese after Tiananmen Square, visas for the Kosovo Albanians, the Bicentennial (big increase in family reunion and refugee intake in late 80s). I believe that this will be true in the future. If the Government feels that the labour force needs to be expanded, it will increase the skilled intake. At some stage in the future, we will no doubt be competing more heavily with other heavy intake nations (Canada, USA, European nations, oil-rich Middle-Eastern countries etc.) for skilled labour as they emerge fully from the GFC. Beyond 2031, it is not unreasonable to think that we may have to compete with Taiwan, Japan, South Korea and Brazil for migrants and more Indians and Chinese will just stay home as the opportunities there become just as attractive. It is also possible Australia will have a recession like we did in the early to mid-90s, and then no one will want to come to Australia.

Of course a larger immigration intake and a bigger Australia requires greater investment in physical and social infrastructure, and our environmental challenges become doubly pressing.

However, as a final note, I’d point out that the sum impact of Australian society on the Australian environment is a factor of the number of people and the impact per person.

Reducing the number of Australians would obviously reduce our total impact. But wouldn’t it be better to focus on our personal environmental footprint? This would require personal sacrifice as well as difficult collective action (the shift to renewables for example), but I feel that the rewards would be worth the effort. It seems to me it would make sense for the debate to focus on these challenges.

Cutting population growth is perhaps just too simple (and unrealistic) a solution.

With thanks to Matthew Deacon for his thoughts on this subject. You can read Matthew’s detailed analysis in our ebook ‘ Three growth markets in Australia’.