I was enjoying a glass of wine with no. 2 son this week when, as a fledgling winemaker/philosopher, he mentioned the struggles of his generation – the “lonely” generation. The fact that the no.2 son had actually purchased the bottle of wine, rather than me, was astonishment enough for the night (and worth a blog in its own right), but his knowledge of demographic cohorts had me intrigued, as did his labelling of millennials as the lonely generation. I had to ask myself are millennials really the “lonely” generation, are teenage and young adult years a lonely stage of life, or are we all simply living in a lonely era?

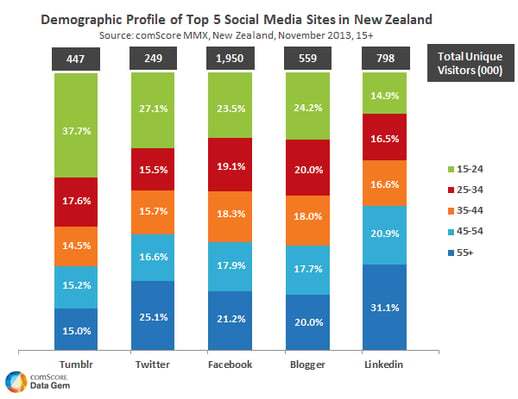

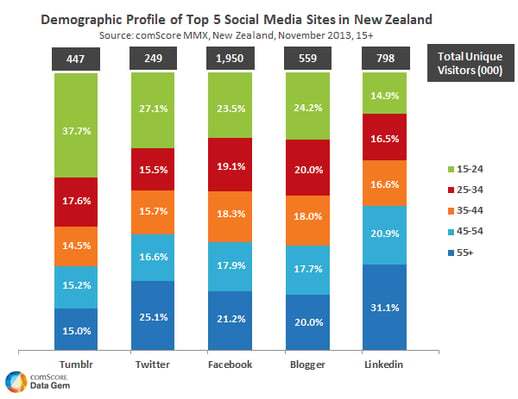

Generation Y make up around 27% of New Zealand’s population and no.2 son was without doubt referring to the paradox of his connected Millennials finding that technology is no substitute for face-to-face interaction. However, one look at the demographic makeup of social media users in

New Zealand reveals that generation Y are not the only connected generation.

Source: http://www.comscore.com/Insights/Data-Mine/Who-uses-Social-Media-in-New-Zealand

Technology does undoubtedly have a huge impact on interpersonal communication, but there are a host of other demographic characteristics that are known to contribute to loneliness. In the 2013 Census nearly a quarter (22.9%) of New Zealand’s population lived alone, 17.8% of all families were

single parents, 8.5% of workers did so from home and 14.5% of those undertaking unpaid work looked after an ill or disabled person at home.

New Zealand also has high levels of transience – between 2008 and 2013 only 41.5% of the New Zealand population did not move. Whether the churn is between suburbs, districts, regions or countries, the potential dislocation from relationships is obvious.

And within the migration patterns teenagers, young adults and young couples with children are much more likely to be mobile as they move for study and work opportunities. So migration is one area where Millennials may have it on other generations at the moment, but it is characteristic more linked to stage of life than generation.

From a wider perspective researchers also note that loneliness is a symptom of unequal societies, and the widening gap between income levels attests to this in New Zealand. Half our working population has an income of less than $28,474.

Source: Statistics New Zealand, Census of Population and Dwellings, 2013

Compiled and presented by .id, the population experts

So we know that technology and various demographic characteristics contribute to loneliness but why does it matter? Quite apart from being an unpleasant emotional feeling, it turns out that there are significant economic and social costs attached to loneliness. People who are lonely find it harder to control their behaviour and are more likely to manifest self-destructive habits. As a result overeating and other eating disorders, alcohol and drug addiction occur more often in lonely people.

Ironically, rather than seek the contact they so desperately need, lonely people are more likely to withdraw from social contact and become further isolated. Research confirms that it is only face-to-face interaction that generates a complex psycho-physical exchange involving body chemistry that enhances cognitive function and physical/social wellbeing.

So those who experience loneliness are also more likely to feel stress, and can struggle to sleep. Lonely people have higher rates of immune and cardiovascular problems and can lack the physical and emotional resilience needed to overcome life challenges like ill health, separation divorce, or redundancy.

Some level of loneliness, at some stage in life is an unavoidable fact of life. There are definitely those with a higher need for support who may experience loneliness – the aged, single parents, those at home caring for someone, people with disabilities, the young and minority groups are examples.

Then there are life changes like moving home or jobs, separation or divorce, kids leaving home or the arrival of a new child that can lead to loneliness. How our towns and cities are designed to facilitate or inhibit connection also has an influence.

Maybe a higher number of generation Y ‘ers do feel lonely, but surely that is more closely link to their stage of life. Personally I think that loneliness is symptomatic of this era. We are social animals in an individualistic society, and whether loneliness is every day or existential, there is a need to re-

energise and revalue face-to-face interaction and community connections. The impact of technology, migration, and an ageing population is irreversible, yet how we are living and interacting can and should be changed. The cost of loneliness at an individual, community and societal level is just too big to ignore.

More reading on the subject? Checkout http://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/content/assets/PDF/publications/the_lonely_society_report.pdf