I used to work with a team of customer service staff who dreaded Māori Language week each year because customers would often react angrily to a Māori salutation. Thankfully that was many years ago and Te Reo Māori is now accepted and respected.

Te Reo Māori became an official language of New Zealand in 1987 and revitalisation efforts started shortly after guided by a vision for Te Reo Māori to grow as “a living language that reflects life and culture in Aotearoa”.

How well is that vision progressing?

The census asks the question “In which language(s) could you have a conversation about a lot of everyday things?” It is a multi-response question.

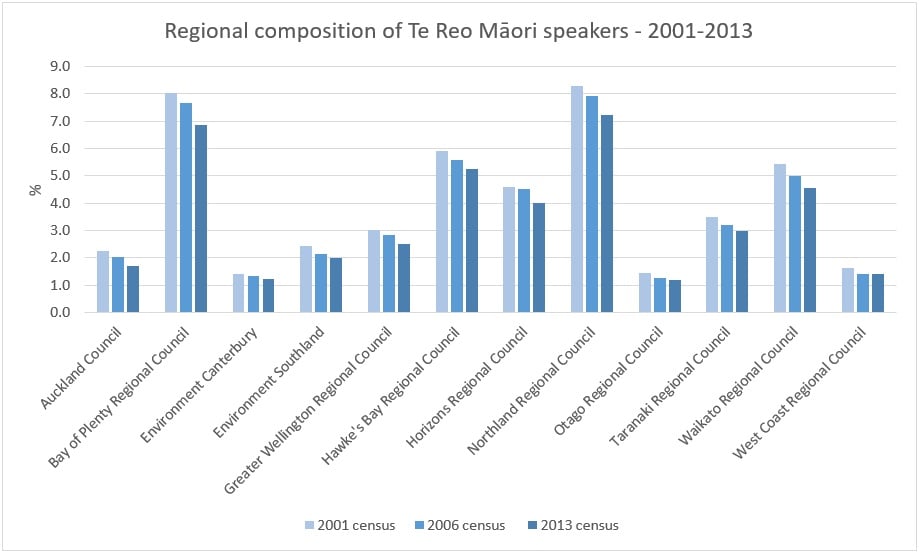

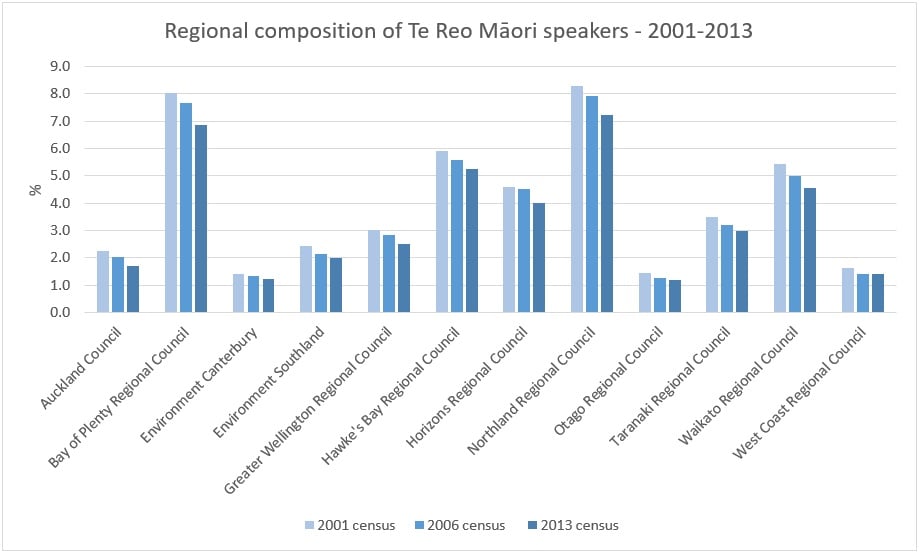

The last three censuses reveal the absolute number of Te Reo speakers in New Zealand is decreasing. The results in percentages reveal a similar story. The chart below confirms that the decline has been experienced across all regions.

Table 1 profiles those speaking only Māori and those speaking Māori and English between the 2006 and 2013 years comparing the progress on the Māori and Non-Māori population. The one area that did experience an increase was with Māori Te Reo speakers who spoke only Māori.

Why is speaking Te Reo Māori on the decline?

New Zealand’s general education curriculum encourages Te Reo Māori from the pre-school level. However the raft of Māori-education initiatives that energetically followed the declaration of Māori as an official language seemed to wane in the 2000s. Kōhanga reo (preschool language ‘nests’) surged in numbers in the 90s followed by the growth of Kura kaupapa Māori (Māori-language immersion schools). However the next decade saw a decline in the number of Kōhanga reo numbers (by 2009 numbers had dropped from a high of 819 in 1993 to 464). In 2009 there were 73 Kura kaupapa Māori schools.

Reassuringly the development of Māori tertiary institutes has continued, most notably with Te Wānanga o Aotearoa which started up in Te Awamutu in 1984. Now with establishments throughout New Zealand, Te Wānanga o Aotearoa was the second largest tertiary education provider in the country with more than 21,000 full-time equivalent students in 2009. Other notable tertiary achievements in Māori tertiary education include Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi in Whakatāne, which attained endorsement in 2004 to teach PhD level courses. Even though it had been operating for just over a decade, Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi is now hailed as a world leader in indigenous universities.

Perhaps the decline in the number of Kōhanga reo and Kura kaupapa Māori schools is part of the reason behind declining numbers of Te Reo Māori speakers in New Zealand. Yet there will be other influences at play. Perhaps young adult Te Reo speakers (as a product of the educational system) have been part of the migrational flow to Australia for work. Between 2006 – 2011 the number of Māori in Australia rose from 92,551 to 128,326 although some of this increase was natural, migration also contributed significantly.

Another explanation might be that the use of Te Reo is becoming more difficult as communities become more ethnically diverse. We know that the New Zealand Māori population has grown in number (604,110 in 2001 c.f. 668,721 in 2013). But at the same time, the proportion of Māori in the total population has actually declined (i.e. from 16.2% to 15.8% in 2013) largely because of immigration.

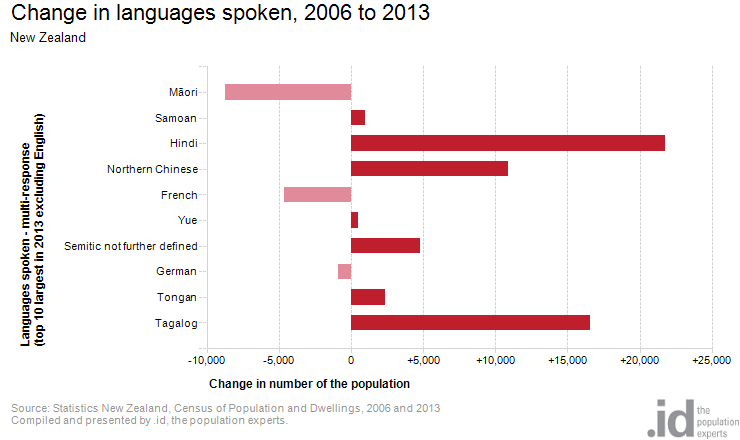

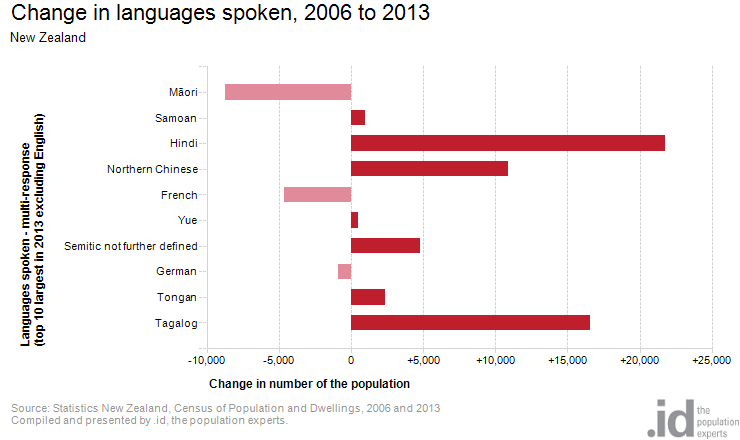

The ethnic makeup of New Zealand experiencing huge change. In 2013 just over one million people living in New Zealand were born overseas (around one in four), and close to a third of that total had arrived in the country within the 5 years prior to 2013. Birthplace data show Indians, Filipinos and Fijians dominating changes. Each of these countries has their own language, the rise of which is evidenced in the following table. Note – Hindi is the preferred official language of India while Tagalog is a major language of the Philippines.

Concluding my ruminations, the vision for Te Reo Māori as “a living language that reflects life and culture in Aotearoa” is a laudable but in practice is proving a difficult challenge. Te Reo Māori is encouraged in all levels and genres of schooling, and even in the local government world a quick glance across council websites finds most councils using Te Reo Māori as part of their council titles and in salutations. Yet the step from a handful of commonly known and used words to level of fluency which could be employed in everyday conversion remains beyond most. What strategies could government employ to make progress?

If reading this, you (like me) have reflected on just how little Te Reo Māori you know, here’s a useful link to get you started – http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/culture/Māori-language-week/100-Māori-words

Nga mihi

.id is a team of population experts, who use a unique combination of online tools and consulting to help organisations decide where and when to locate their facilities and services, to meet the needs of changing populations. Access our free demographic resources here.